Written by Alondra Perez. Graphic by Sophie Levy.

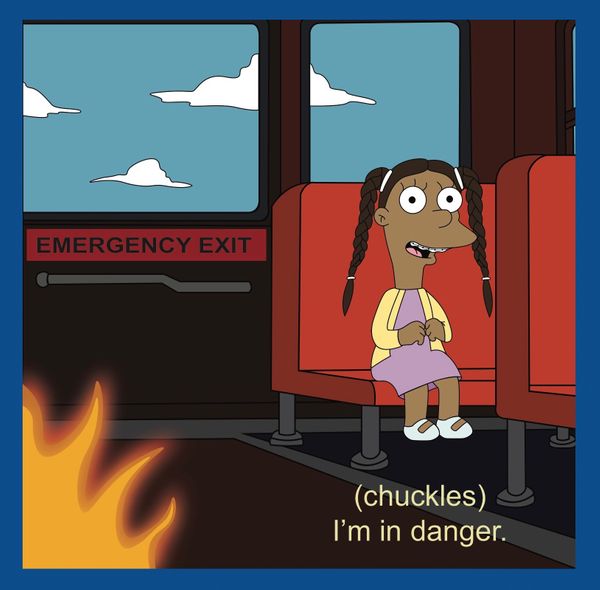

The pressure to be graceful has often trapped my voice and paralyzed my limbs. I have smiled in the face of danger thinking that my pretty teeth would save me.

A couple of summers ago, I was invited to my friend Laura’s parent’s house on Long Island. She’s white. I was invited along with some other classmates, two white girls: Jane and Erica and one Asian girl, Abbie. We all met during our actor training in New York City the year before. We took the train over to Long Island from Port Authority. During the ride, we talked about the use of nigga. Jane recalled it being used frequently by white people in Florida, where she grew up. She admitted to having said it before but no longer doing so, stating that she now understood she should not say it. Laura felt that if white people couldn’t say it, then everyone should stop using it altogether. Erica was on the fence and willing to agree with whatever made her seem most liberal and least problematic. Abbie said white people couldn’t say it. The conversation was laid to rest as I established that only Black people could choose when, where and how to use it. It’s not for white people. Our conversation shadowed me as we walked from the train station to Laura’s house.

The rest of the day was fine. We ate hot dogs and chips, I think. I met Laura’s father, an outgoing and sometimes imposing white man. Laura’s mom was petite and didn’t talk too much. I finally met Laura’s brother, whom, she often mentioned, was an avid Bernie supporter. He hung around in the shadows, though, on the outskirts of our conversations. We did not talk much.

Night fell on all of us as we sat around a fire, with Laura to my left, her dad to my right and the rest of the girls across from us. Her dad was drinking and speaking loudly. I remember him being generally oblivious to how much space he was taking up. The flames in the pit moved slowly. I had also been drinking so I went back into the house to use the bathroom on the 2nd floor. It was nice, it had purple walls. There was a sun pendant hanging somewhere in there, I don’t really remember. The lighting was warm and I was feeling myself. I thought me and my slick back bun were stunning. I marveled at myself in the mirror for some minutes before heading back outside. As I approached the fire, I heard Erica try, once again, to remain neutral enough to not be problematic. Erica is notorious for subtly distancing herself from problematic opinions without actually saying she disagrees.

Our previous conversation had been resurrected in my absence. I sank in my seat already exhausted by the prospect of having to speak for every Black person ever.

“I just think that if Black people don’t want white people to say nigga then they should not put it in their songs” said Laura’s dad.

I didn’t know how long before my arrival the conversation had started but I felt a collective stillness follow this statement. Either my friends were shocked that he said nigga or they were shocked that he said it around me.

“Why can’t I say nigga?”

He said it again and all of my friends stared at me for far too long before reacting.

Finally, someone mumbled you can’t say that.

“Okay, well if white people can’t say nigga then Black people should stop using it.” He said.

I might have said something. I don’t remember.

I had stumbled upon a very white conversation. A very normal white liberal conversation. I think if I had not been in that space, everyone would have echoed his question about white inclusion in Black vernacular. But my presence rendered everyone silent.

He continued on his baseless tirade. Laura’s dad was deeply offended that Black people wouldn’t let him say nigga in peace. I looked over at Laura with pleading eyes. Laura kept her eyes on the fire. I saw her shrink for the first time. The rest of the girls looked past our host, through the fire and straight at me. They waited for my reaction, waited for me to lead them in my defense. But I was paralyzed by grace and could not speak as loudly as I wanted to.

“Nigga.” He was daring me to deny him the right to say it. In his house. In front of his daughter, my friend.

I felt the weight of my entire body. My ears were hot. The flames in the pit looked different. Laura’s father was taking up too much space, he was bigger than he needed to be and he was too close to my face. I did what most women know how to do: I calculated the likelihood of being hurt if I were vocal. After calculating the proximity of his body to mine and the distance from his house to the train, I gave up. I sank into grace.

The train station may have been closer and his body may have been further from mine but in my memory of this experience everything I needed was really far away and the closest things to me were useless.

I watched my friends watch me see them for the first time.

“Dad, you can’t say that!” Laura’s brother yelled from his bedroom window.

I almost laughed at the absurdity of it all; but I didn’t, fear seized my laughter. I wanted to evaporate.

I got home that night and tried to figure out how much of what happened was my fault. I realized my white friends had long ago told me what kind of allies they were, but I had attributed their comments to their ignorance and said nothing because, though I was offended, I did not feel implicated. I knew that if I had higher expectations of my white friends, I’d have none.

White supremacy guilts Black people for however they choose to survive within its reigns. It mocks Black people for surviving in silence and grace and condemns them for resisting and fighting. But that fight, in my friends’ house, where I was a guest, where I was outnumbered by white solidarity, was not mine to fight.

I was not so much traumatized by Laura’s father berating me with nigga as I was traumatized by Laura’s inability to tell him to stop. I had learned to survive fear and discomfort with a smile on my face and Laura had learned to avoid discomfort and confrontation at anyone’s expense.

Yet, even in my fear and discomfort, I was in a position of privilege as a light-skin Black Latina.

Imagine a version of that night where the young woman sitting next to her friends’ racist father is darker, has less ambiguous features than I and a functioning voice box. That she had the courage to say something. That she might have left the house and walked 20 minutes to the train station in the middle of the night, in a white neighborhood on Long Island. But if I had been a Black man of any hue, would Laura’s dad have had the confidence to play devil’s advocate on a non-negotiable?

If my friends perceived less distance between my blackness and Laura’s dad’s racist antics, would they have, then, been compelled to intervene?

The racist things white people say around me are because of and in spite of my blackness. My blackness and I are: palatable, non-threatening, inviting and ambiguous. Bringing me into a predominantly white space or home makes white people feel like they’ve done the work. They get comfortable. They ask racist questions and make racist remarks assuming that I’ll be understanding of their curiosity and slip-ups because they are above reproach. They have, after all, invited one Black person into their home, company or institution. My presence validates them and in their arrogance, they expose themselves.

Laura’s dad waited a long time for the opportunity I let him take that night. The fervor with which he said nigga was the result of years of being shamed into silence. That he did not say it around other Black people, was not because he did not want to, it was because, for white people, goodness is of most importance. Being good around Black people is more important for white people, than not being racist around each other.

Goodness is a performance contingent on who’s in the audience. It’s contingent on the social location and power dynamics between the onlookers and the performer. This audience was composed of white solidarity. White, male, mildly inebriated and in front of his daughters’ friends, Laura’s dad had the optimal social location. No one would hold him accountable or dispute his goodness.

White people hate being told what to do; but they especially hate being told who they are. I know, if ever Laura’s father reads this, he will likely talk about how his mother was a Spanish immigrant and how he married an Italian woman. He’ll talk about his love for music from all corners of the world. He might argue that he is a citizen of the world. Laura’s dad might even say he doesn’t remember yelling nigga into the night - and it’s likely he doesn’t. Laura’s dad would be offended that I did not recognize the curious intention behind his racist question. Racism has a way of being swallowed by intention in a uniform blob of goodness.

White people don’t like to take responsibility for each other anymore than they like taking responsibility for themselves. But racism and white supremacy would not exist without white solidarity. Racist white people cannot exist without the silent white people who enable them.

All the silent white people who watched the fire that night, have posted on Instagram in support of Black Lives Matter, ally ship and justice.

I have seen a Recommended Reading List to Combat Racism posted by a white person who said to me:

“Why are Black people always complaining? Why can’t they shut the fuck up? Just don’t resist and maybe the cops won’t kill you.”

The white Latina who said “I hate J. Cole he is always bitching, like why do you always need to talk about police brutality? No one wants to hear that. We get it.” has not stopped posting about defunding the NYPD and police brutality.

It is not socially acceptable to be silent in this moment and for that reason I don’t trust everyone who’s talking.

All of you fall somewhere around the fire.

A lot of you are like Jane, Erica and Abbie sitting in the periphery of trauma, rejoicing in the fact that you are not the one inciting the violence. A lot of you are like Laura’s father excited to be good in public but bursting at the seams with racist ideologies. Most of you are like Laura, though, paralyzed by your social location and unable to take your activism from Instagram to your kitchen table.

Too many of you have fallen into the habit of looking through the fire at the only Black person in the room hoping that they advocate for themselves so that you don’t have to.

And a lot of your Black friends are like me, held hostage by grace, dangling above the flames, trying to survive the violence.

Check LONYC weekly our take on: creative writing, politics, photography, food, fashion, film, and music. Follow us, feel the vibe @laidoffny.

Get to know Alondra better, @alondrapilar for all her latest creative endeavours.

For more thought provoking graphics check out @art_by_slevy.