In our first official act as the new ruling party of Laid Off NYC, we asked writers to choose cultural objects—pieces of art, memes, fashion trends—and use them to reflect on their years. 2020 was tough on all of us, but these small pleasures, some guilty, some high-brow, helped us get through it. Today we wax on Winston Churchill, Superbad, bike shorts, Sorry (the band), Nashville (the movie), Anthony Bourdain, André Kertész and Roman Holiday.

Winston Churchill had a bad year. Last summer, when the George Floyd protests crossed the Atlantic, Churchill, more than any other figure that represented the white-male hegemony that defined the United Kingdom (and still does), was the focus of ire. Churchill was an unabashed racist and imperialist. He spoke plainly about the need to subdue protesting Iraqis with tear gas, and viewed Indians with a particular cruelty that surpassed any of his other prejudices. Statues were defaced, to the point that authorities chose to encase Parliament Square’s monument to the late prime minister in a metal box.

My yearly itch for World War II history had flared up again in March when Churchill’s famous anthology, The Second World War, crossed my path. Until then, I had mostly read work from those who were “outside the room”—journalists, historians. I actively avoided accounts from those who had held the levers of power. What, in their subjective, agenda-ridden prose, would they tell me about what happened that I could believe?

It wasn’t until, curious due to the constant reflection over and correction of Churchill’s legacy this summer, I read his anthology and recognized its value. It is without a doubt the most biased piece of writing I have ever read about World War II. Churchill was quick to assign blame and attribute individual failings to cultural stereotypes. He downplayed his own faults with sarcastic arrogance and muted his successes with false modesty. Save for a few noble confessions and quiet, minute admissions, he saw the path to World War II as plainly as he saw how it would end, which, in his mind, was exactly as he predicted. He was a man writing his own history, knowing that it would be accepted as the record. The result is a modern Bellum Gallicum, Caesar’s firsthand account of the Gallic Wars.

It was exactly what I needed. While most of the work I read this year tried to contextualize our times by comparing them to the past or imagining how today would be remembered tomorrow, Churchill’s The Second World War was in the now, filled with day-to-day trivialities that provided the reader a window to the past. One can write an entire series about how World War II ushered the United States to the status of world power. But no book can encapsulate that shift quite like one paragraph of Churchill expressing his fear of a transatlantic flight despite the insistence of Franklin D. Roosevelt, choosing instead to take an arcane charter. There is plenty of literature about how different nations approached the war, their calculations and final decisions. But it doesn’t place you among the vulgar notions of race and culture that were used to explain the actions of an entire people at that time.

As hard as Churchill is to read, what he writes is true. It’s not how the world is, but it’s how we have lived for centuries. Churchill was a man of his moment; he did not hide it. At a time when we are pressured to relate our current moment to the past or consider how it will be remembered, we must be careful not to disserve those who will try to understand our world when we are gone. By writing our own histories, we become benchmarks of progress.

Nostalgia and ease ruled my media consumption in 2020. I would think about finishing one of the hundred or so books in my room, maybe starting a new show or picking up a new hobby—I managed to cross-stitch half of Timothee Chalamet’s face and make one collage. But instead, I’d rewatch Superbad.

Superbad, for those of you who did not turn 13 in 2007, as I did, is the first of many collaborations between writing partners Seth Rogan and Evan Goldberg, directed by Judd Apatow. It stars Jonah Hill, Michael Cera, Christopher Mintz-Plasse, Emma Stone, Seth Rogan and Bill Hader. It’s a comedy about getting drunk and trying to lose your virginity. Ultimately, though, the real sex turns out to be the friends you make along the way.

Basically, Superbad is a straight white male bro comedy, very much of its era. On the surface it’s about trying to sleep with women; dig a little deeper and it’s about male friendship, like many movies of its ilk. Some of it holds up, like the joke, “No one’s gotten a handjob in cargo shorts since ‘Nam,” and some of it doesn’t, like the homophobic slurs. All of it, though, feels like being a teenager in the late 2000s.

My parents loved Superbad when it came out, but they thought it was way too filthy for me. They didn’t even watch it on our TV; they sequestered themselves in another room, watching on a laptop. But I desperately wanted to see it, and 13-year-olds always find a way. I watched it on my friend’s iPod Touch in 15-minute intervals, sitting by our lockers before school. It took a full week. It was worth it. I loved it then, and I love it now.

Early-to-late-aughts bro comedy informed a lot of what I think is funny today. I still like dick jokes, and Judd Apatow movies, and stories about getting high that don’t really go anywhere. Superbad is one of the pieces of media that, when I first experienced it in middle school, cracked my tiny brain open. Anchorman, Lonely Island songs, Wet Hot American Summer—all that was revelatory to me. “This,” I thought, “now this is comedy.” I still kind of think that.

2020 was full of Zoom table reads and reunions for charity. The cast of Superbad was no exception. They reunited, and I donated to Wisconsin Democrats so I could watch. It was a true delight. I learned that the main cast bullied each other and acted like idiots on set, because they were basically kids—exactly as I expected.

I tried to use early quarantine to learn new things. I tried to watch classic movies I hadn’t seen, read some books I’d been meaning to get to, watch documentaries people at parties had recommended. And I did, for a while. But what resonated with me in 2020 was, essentially, anything I didn’t need to think about. I wanted to watch movies I’d already seen. I wanted to laugh at jokes I’d been laughing at for over a decade. I wanted to turn my brain all the way off and watch dudes make dick jokes. I wanted to watch Superbad, so that’s what I did.

Bike shorts had made their way into lay-women’s closets by summer 2018, but the garment achieved an entirely new mass-market status in 2020. Quarantine seemed to produce in us a sort of “snow-day effect,” one symptom of which was a sudden and collective need to live our lives exclusively in elastic waistbands.

By early May, at which point I had been involuntarily celibate for exactly two months, I began funnelling all of my hedonism into daily, hour-long walks around my neighborhood. Bike shorts, naturally, became the perfect prop to satisfy both my reignited interest in sexual attention and my new, comfort-first approach to life. Stretchy, form-fitting, and eye-catching (though mostly by negation, in the contours they reveal), bike shorts allowed me to indulge in a personal fanfic of my own sporty sex appeal. And, masked and sunglass-clad, I didn’t even have to take responsibility for this indulgence: I could be both exposed and anonymous at once.

If it was a cheap thrill, it was nonetheless thrilling. Having previously shelved my shorts-wearing comfortability at age 19, busting out bike shorts now seemed to betray a bodily confidence that I, in reality, rarely actually harbored. Newly uninhibited—and conveniently justified by the ever-worsening humidity of late July—I began ordering progressively shorter inseams. I pranced around my apartment in a pair of Alo Yoga micro-shorts and a hot pink sports bra; asked if this was appropriate to wear outside, my roommate said, “I think it would look really good with a shirt.”

By late-August, I was feeling out of control. After too many to-go margaritas and half-assed home workouts, I was looking and feeling not so good. The messaging for self-acceptance during “these unprecedented times” now rang hollow; it was time to restore some dignity to my self-presentation. Besides, self-exposure wasn’t even subversive anymore, now that data had gutted the concept of “transparency.” As it turned out, being seen (both algorithmically and corporeally) had diminishing returns: now it felt passe, and maybe even a little gross. And so, come Labor Day, every single pair of my bike shorts were formally demoted from their coveted position next to my tiny tops to my bottom drawer full of ratty workout clothes. There they will reside in perpetuity.

Unlike the nap dress, the other breakout star of 2020, bike shorts do not evoke any sort of timeless femininity. Instead, they seem to firehose the public with a too-loud, too-narrow literal representation of one’s physical form, all the while conforming to the fluctuations—healthy and also not—of one’s waistline. While this malleability may have been welcome in early quarantine, when we struggled mentally and physically to adjust to our new reality, we ought to reacquaint ourselves with the ideals of discipline and general self-respect. And so, in 2021, it is my opinion that house clothes—and any item that approximates them in construction—should remain squarely inside the home.

Lester Bangs dreamt of a basement containing every album ever made. Now, with streaming, that dream has been almost realized. Not every album is available, but the ability to choose from over 50 million songs without having to buy or download any of them is pretty close to Bangs’ vision of a world of limitless listening. For listeners like me, though, the sheer volume of music so easily available can be overwhelming. “What should I listen to today?” shouldn’t be a daunting question, but the ability to choose practically anything can make it one.

Around 2018, I quit worrying about new releases. I still keep up with new music, but it’s a delayed process. Albums, new and old, are saved to my Spotify library like people waiting for their number to be called at a DMV, and sometimes they can sit there for quite a while.

Sorry’s 925 is a record I’ve had saved since its release in late March, and with just two days left in 2020, I finally gave it a listen. I’m not usually one to keep an album in constant rotation for more than a day, but 925’s off-kilter rock ended up being the only thing I listened to for almost two weeks straight.

Sorry is Asha Lorenz and Louis O’Bryen, two childhood friends who sing restless songs about the unsatisfactory yet enchanting present. Alluring strangers are admired from afar; relationships are formed and fucked up; confusion and self-doubt contort the mind; and the wheels of capitalism continue to turn, indifferent to human emotion.

Artsy punk and bedroom pop provide the musical backdrop, but Sorry’s sound is distinctly of an age where access to the internet has destroyed all genre limitations. Splatters of jazz and trip-hop appear throughout 925, throwing wrenches into otherwise-conventional indie songs. It’s a life-affirming record but never too affectionate, and it makes me smile and wince in equal parts.

By happenstance, I called 925’s number from my Spotify DMV on December 30th. One place below it sits Special Request’s Vortex, an album I’ve been meaning to listen to for over a year-and-a-half. 925 might have suffered the same fate, but on that day, something drew me to it. There were albums I listened to more than 925 this year, but Sorry’s record struck a nerve that needed striking. It harkens back to a pre-COVID playfulness I desperately want to relive—imperfect, but free of the torrential worry, suffering, and distance we experienced in 2020. Fate in the age of algorithms is predictably unpredictable, but 925 felt like an intervention.

In late March, when the news was terrifying and terrible, and my sanity felt like a house of cards that could topple at any moment, I watched Roman Holiday. I don’t feel very bad about spoiling the ending of a movie that came out in 1953, so I’ll tell you what happens:

Audrey Hepburn plays the princess of an Obscure European Nation on a royal tour that wraps up in Rome. She is the type of exhausted and bored where bursting into tears is inevitable. Her doctor gives her some sleeping medication, but she has an adverse reaction and, in a kind of delirium, wanders out of the embassy where she is staying and runs into Gregory Peck.

Gregory Peck is a chic American journalist who manages to wear a suit and tie in the middle of summer and somehow still look totally at ease. He initially believes he has stumbled upon a wayward young woman who had too much to drink, and he lets her sleep in his apartment (she takes the bed, he takes the couch). In the morning, he realizes she is the very princess about whom his editor has tasked him to write a story. He plays dumb and calls a photographer, while Audrey Hepburn decides to take advantage of the situation and have a day of anonymous fun. She cuts her hair short, rides around on the back of Gregory Peck’s Vespa, sees the sights, and goes dancing.

From the beginning, we know the situation is temporary. Even as Gregory Peck’s exasperated humoring of the naive young princess gives way to affection and then to love, the audience understands that Audrey Hepburn will eventually go back to her real life. Gregory Peck returns her to the embassy and they kiss before she leaves. The next day, she sees him at a press conference; she is surprised, but not betrayed in the way you might expect. He doesn’t file his story, and the photographer gives her the photos he took, and she is soon ushered out of the room. Gregory Peck waits long after the rest of the members of the press leave, but she doesn’t re-appear. The movie ends with Gregory Peck walking down the long hall out of the embassy, flanked by marble pillars and oil paintings. He slips his hands into the pockets of his loose-fitting, pinstriped suit (in, frankly, a very dreamy way). We wait and wait for him to turn back, or for Audrey Hepburn to run after him. She never does.

It’s encouraging to think that, for better or for worse, nothing lasts forever. Holidays come to a close, affairs end, hair grows back. But in the months that followed my viewing, when I began to realize that the news would remain terrifying and terrible for some time, I remembered the way Gregory Peck smiles to himself as he walks away, and the feeling that one has at the end of Roman Holiday that, even though our protagonists have gone their separate ways, there’s something connecting them.

I started to think about the way almost everything lingers on, in one way or another, and it’s that thought that’s become my biggest comfort. On the worst days of 2020 it was difficult not to get lost in the melancholy of all the little things I missed—the birthdays, the graduations, the daily joys and anxieties that I wasn’t there for—and the events of far greater magnitude that other people missed. On those days, I think about Roman Holiday and remind myself that we are all eternally, inescapably intertwined.

In 2013 I found myself in China, a 19-year-old boy aspiring to make my mark in the lineage of well-traveled American men. I imagined myself Ernest Hemingway or Anthony Bourdain, though, in reality, I was a teenager taking videos of my friend and me spoofing CNN’s Parts Unknown over steaming hot pot, succulent Peking duck, copious bowls of roadside noodles bubbling in perfect broth. I had read Bourdain’s Kitchen Confidential on the plane, and I dreamt of achieving transcendent moments of culinary delight in China’s vast countrysides and the crevices of its futuristic megalopolises.

When Bourdain died in 2018, I purposely neglected to watch or read any of his work. But last year, out of a surface-level desire to travel beyond my hometown of Indianapolis and, later, my small Brooklyn apartment, I started rewatching No Reservations, Bourdain’s show on Travel Channel, which ran from 2005 to 2012. The show had just enough distance from our current dystopia to elicit the perfect dose of nostalgia.

In the Amazon, Bourdain silently contemplates the profoundly complex indigenous flavors he encounters. He acknowledges the near hallucinatory taste of fresh bacuri, pitaya, and biriba. I, on the other hand, was taking in the kaleidoscope flavors of Skinny Pop, Wheat Thins, and rice cakes. There was an obvious disconnect between lockdown takeout and Bourdain’s exotic meals. But it was his respect and consideration for others that struck me, not the distant locales he visited. His reverence for strangers as they open their homes to him and his crew felt completely antithetical to the behavior I was seeing daily. Without a whiff of sentimentality, he was grateful.

“Since my first trip here nearly ten years ago, I have been to nearly every corner of the globe, and I’m not gonna say, as much as I’d like to believe it, that I’ve gotten any smarter,” Bourdain says in the final moments of his journey in Cambodia. “After a while, even the most beautiful scenery threatens to become moving wallpaper. Background. But other times, it all seems to come together—the work, the play, all the places I’ve been. Where I am now. A happy, stupid, wonderful confluence of events. Rice paddies whipping by, the music in your skull – just right. If something profound ain’t happening, at least it feels like it is.”

Bourdain’s words rang both painfully and euphorically true during the deepest moments of quarantine. The pandemic has been unequivocally strange. Moments of profound lucidity have been followed by even deeper confusion. At my best, I’ve been more appreciative than ever before. At my worst, I’ve been at my most petulant and self-absorbed. Ask my mother; she’ll tell you all about it. This glimpse at clarity hit hardest after long, meditative runs and lingered over shared meals among loved ones. I hadn’t traveled to the other side of the earth with Bourdain, but that constant feeling that I was on the precipice of understanding who I was—only to have that feeling slip away—bound me to his sentiment.

When I was in college, I bought Looking at Photographs: 100 Pictures from the Collection of the Museum of Modern Art. John Szarkowski, a critic who directed the photography collection at MoMA from 1962 to 1991, writes in the introduction that the book is “a tiny part of photography's achievement." Published in 1973, the book collects black-and-white pictures from a hundred different photographers, accompanied by brief comments by Szarkowski. It opens with the daguerreotype "Mother and Daughter,” taken by William Shew sometime in the late 19th century, and closes with a landscape taken by Henry Wessel Jr. in 1968. About the daguerreotype, Szarkowski writes that it should be approached like a secret; about the landscape he says that a picture of a mountain, if it’s good, can have “a specific and unique meaning.”

Last year, as I worked on different photography projects and wrote about isolation and lockdowns, I would go back to this old book and open it at random. The images in the book remind the viewer that photography is not only a memento or a medium that captures painful realities; it is also an art that can bring joy. This is particularly true in the only picture by André Kertész collected in the book. In "Montmartre," Kertész captures simple lines and shadows created by the railings of a stair in Paris “in which a pedestrian dangles like a fly,” as Szarkowski describes it. The picture is a celebration of simplicity. There is nothing complex here; it is pure visual enjoyment. Looking at the picture I can imagine myself walking to the stairs and becoming that person dangling like a fly.

What we see is composed by lights and shadows; photographers like Kertész remind us there is pleasure to be found in the contemplation of light. Whenever I look at this picture I briefly feel optimistic and joyful. Szarkowski felt the same way and offered an explanation: "There is in the work of Kertész another quality less easily analyzed, but surely no less important. It is a sense of the sweetness of life, a free and childlike pleasure in the beauty of the world and the preciousness of sight." In my mind, this is what justifies photography—the capacity to capture the sweetness and simplicity of life. During a year when sweetness and simplicity seemed nowhere to be found, Looking at Photographs did the trick.

In college, I took a course on James Joyce’s Ulysses in which my professor required us to keep a running list of every character who cropped up in the novel. Within a hundred pages, my list had overflowed. I could no more distinguish one name from another, and the novel remained as dense and abstruse as before.

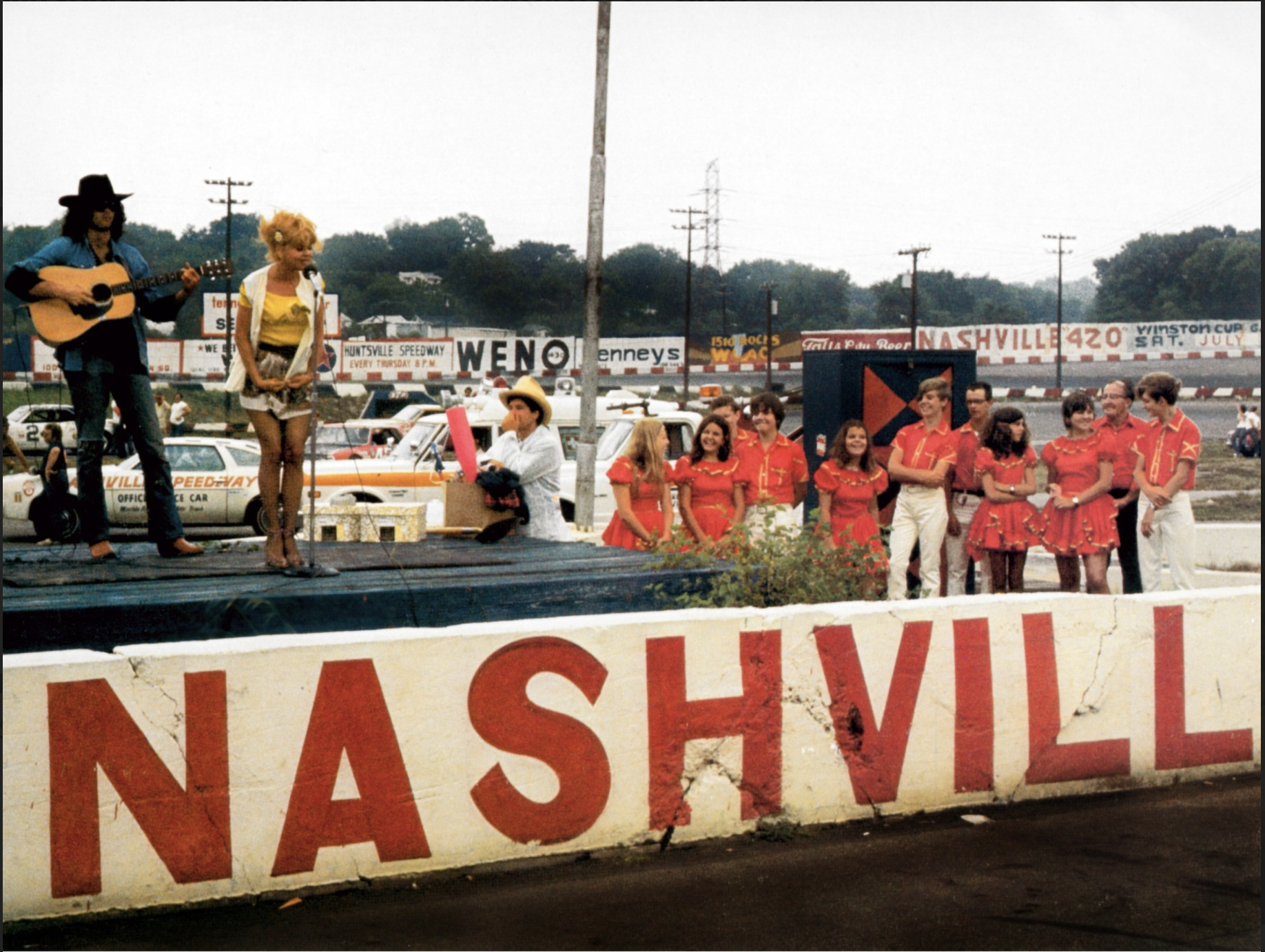

A similar technique might have been useful for Robert Altman’s spectacular ensemble film Nashville, which turned forty-five last year, and which I watched on New Year’s Eve. If today’s films tend to be taut and palatable—a few central characters, a formulaic plot with little room for diversion or intrigue—Nashville is the opposite: a knotty, intentionally graceless film whose plotlines overlap and deviate, and whose Joycean use of character evokes the cultural mania of the ‘70s. A group of disparate figures converges on Nashville, Tennessee in the lead-up to the 1976 presidential election: country singers, managers, groupies, aspiring stars, journalists, politicians, both working-class and wealthy Southerners—all hungry, it seems, for fame and power, the synthetic promises of American exceptionalism. Keeping track of the characters’ stories can be dizzying—I often found myself scrambling for the remote—but at its core, Nashville is a frothy, buoyant film, not an impenetrable one. That it’s also a musical keeps the mood breezy: Many of the songs, even the blatantly satirical ones, are also genuinely affecting and well-written.

Underneath that vim and vigor, Nashville’s critiques of American culture are searing, and more than a little prophetic. The film is punctuated by the demagogic speeches of an independent presidential candidate, Hal Phillip Walker—never seen on-screen, though a variety show fundraiser for Walker serves as a backdrop for the film’s fiery conclusion. Walker wants to drain the swamp; Nashville’s stars and wannabes care more about image and spectacle than populism (most of them agree to perform for Walker without knowing who he is).

Today, when mainstream films attempt a political message, the results are often anemic: Think of Aaron Sorkin’s The Trial of the Chicago Seven, with its feeble entreatment to centrism and whitewashed depiction of the American left. Nashville takes no particular stance, but Altman is cutting where it counts. In the film’s final scene, a lone gunman shoots the country star Barbara Jean, and her co-star, Haven Hamilton, bellows, “This isn’t Dallas, this is Nashville!” That line doesn’t sound too different from some of the sentiments expressed after last week’s riot at the Capitol. “This is America,” commentators said gravely, over images of Confederate flags hoisted in the Rotunda, “not a war-torn country.” But as Nashville suggests, violence is endemic to America, intimately tied to a broken political system, and to our national fixations: a lust for the theatrical, for delusions of grandeur, for strident egotism and ill-gotten gains. It may be that only a film as chaotic and clamorous as Nashville can capture the full spread of American neuroses (and their frequently disastrous effects). It’s a treat of a film, with an unforgiving edge. I hardly noticed when the clock struck twelve, and a new year—in the same America—began.