by Jda S.G.

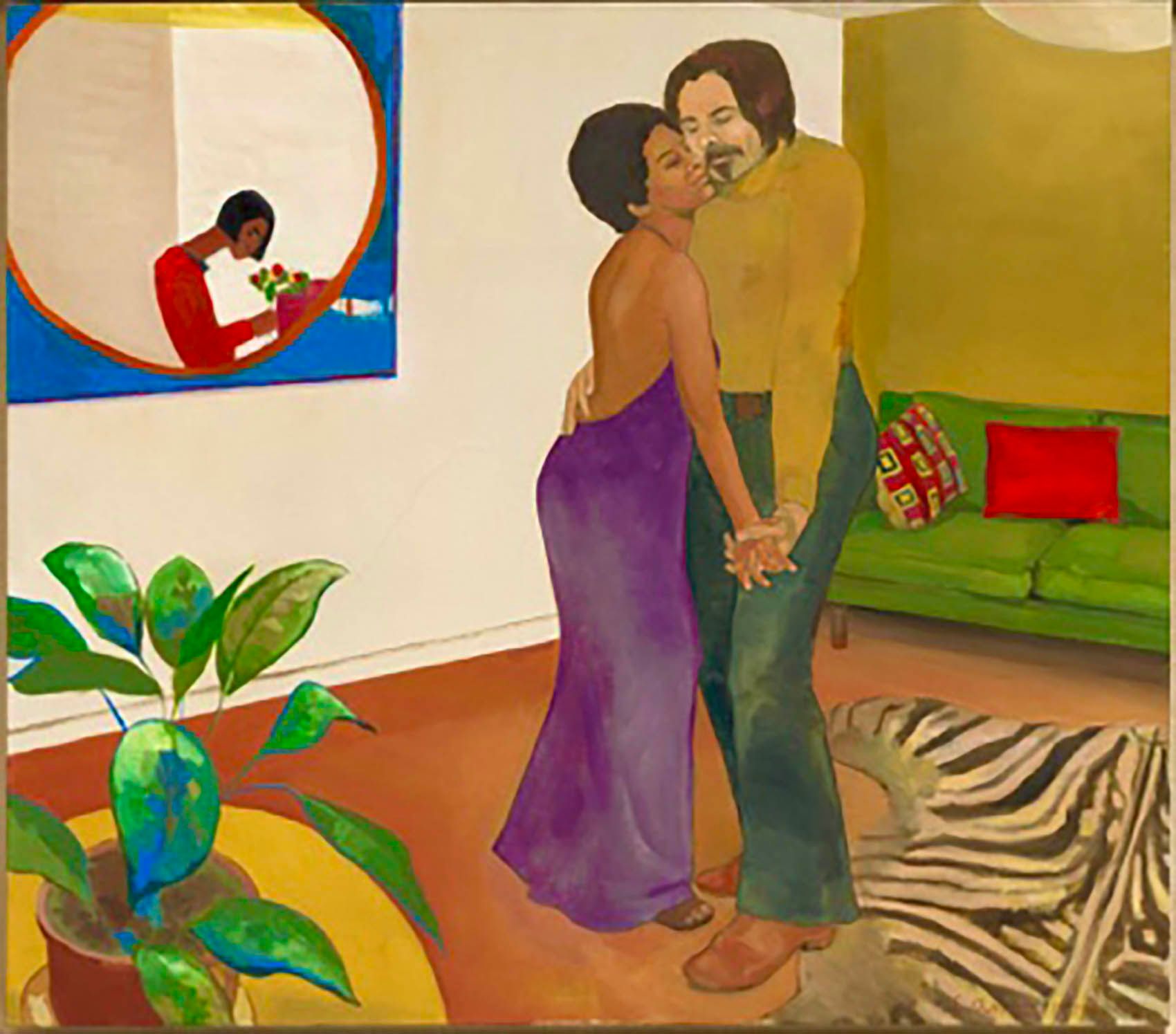

A few years ago, I saw a picture of a college friend and her beau on Instagram. She was queer like me, and her partner was nonbinary, like mine. She added the hashtag “#blacklove” to the caption. I clicked it. My screen shifted to a mosaic of mostly straight Black couples in varying forms of embrace, posing like superheroes or megachurch pastors and their wives. I was in love and I am Black. But my lover was not Black. Did it mean that my relationship was not “Black love?” The images initially fascinated me, but soon gave way to unease. I did not trust my own estimations about what I understood “Black love” to be.

To think that there existed some virtuous Black experience I could not access without another Black person upset me. Why wasn’t my Blackness enough? This feeling of not being enough reminded me of high school, where some Black schoolmates thought the way I talked, dressed, or acted diminished my Blackness. I came to realize they did not act out of malice. Policing each other’s Blackness was but another iteration of how racism manifests within racialized groups. We became friends eventually and supported each other at our majority-white private school, where despite our individuality, we all had to deal with the same systemic prejudices and implicit biases of a white education system. Here I was, over a decade later, feeling like a teenager in the cafeteria, unsure of which lunch table to join.

Childhood memories aside, I wanted to discern the source of my discomfort with the term, so I took to Facebook to poll my Black friends. With one photo of a Black woman with a white man, and another of a Black woman with a Black man, I asked which image represented “Black love” and why. Eleven of thirteen commenters described “Black love” as a romantic relationship between two Black people. My poll results paired with the images I saw on Instagram revealed that “Black love” was not just a cute social media tag, but an ideology, one whose raison d’etre I was determined to understand. Ostensibly, “Black love” is a powerful declaration of pride from a minority racial group. I’d come to find, however, that the true logic supporting this ideology concedes to the same racist assumptions it's trying to disprove.

Over the course of centuries, the media—from the first minstrel shows to radio plays—have played a dominant role in advancing the narrative that Black people were innately irascible and lascivious in ways that made us simultaneously unsuitable for partnerships with white people and detestable to each other. Who can forget the ghoulish caricatures of Black men and the pseudo-terrified white women who claimed sexual assault by the men’s mere presence in The Birth of a Nation (1915), or the very real lies white women told that led to lynchings? By the thirties, roles for Black characters somewhat expanded from hyper-visible bogeymen to invisible aromantic caretakers, like Walker, the tap-dancing butler in The Little Colonel (1935) or Mammy, the housekeeper from Gone With The Wind (1939). Starting in the 1960s, when Black actors began playing romantic leads, it was often with a white love interest, as in Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967) and Mahogany (1975). The cultural takeaway: Black romance was most socially palatable when it included non-Black (mostly white) partners. It wasn’t until the early nineties that a steady succession of titles featured all-Black romantic leads. Films like Poetic Justice (1995), Love Jones (1997), How Stella Got Her Groove Back (1998), and Love & Basketball (2000) portrayed for a new generation of Black media consumers the same kind of fulfilling and complex love stories that seemed to be a white actor’s birthright.

My poll went live at midnight on Friday, February 15. By Saturday morning, I had received about five thoughtful opinions. One of the longest comments came from a high school friend, Rushel, who at the time was dating a white man. She said the term “is fighting against self-hatred that many Black people grew up with.” She went on to highlight how this internalized racism championed interracial couples as more radical than Black couples, with the former used as a barometer for racial progress. She closed: “And so while all lives matter—we still need to chant black lives matter. And while all love is love—we still need to celebrate the space two black people make to love each other fiercely.” Britt, another Black woman friend, said, “the only ‘Black love’ I have is for myself. Often black men throw around ‘Black love’ to shame black women who dared to date other races, to boot.” How could one idea be both symbolic of pride in collective Blackness and a cudgel of shame against Black individuals?

One of the main arguments to support the exclusiveness of “Black love” is that it is an act of resistance in the face of white supremacy. Black actors Daniel Kaluuya and Jodie Turner-Smith—titular romantic leads of the 2018 film Queen & Slim—have both asserted this in an interview about the film. Op-eds and reviews about contemporary films centering Black romance like Moonlight (2016) and If Beale Street Could Talk (2019) all describe “Black love” as revolutionary. And they’re right. Seeing nuanced Black romance on the silver screen—especially gay, Black romance, which is taboo in many Black communities—is a radical change in an industry where such portrayals did not exist. But glorifying these images of Black couples, beyond how they remedy the lack of representation, implies that to date a person who isn’t Black contributes to the myth that Black people are not desirable.

We often think of internalized racism as disliking the aspects of ourselves white society degrades. Rarely do we think of it as embracing the racist standards by which white society expects us to perform. And yet, at its core, “Black love” absorbs white standards and mirrors them back to us. “Black love” says: Since whiteness expects us to hate ourselves to the point of rejecting partnerships with each other, to counter that expectation, we must prioritize those very partnerships. And so, the corollary to framing “Black love” as a protest, the cudgel of shame that Britt identified, is that a Black person who dates non-Black people does so intentionally out of contempt for Blackness. While this may be the case for some people, it is certainly not the case for all. Black people cannot, in the same breath, insist that we are not a monolith and support essentialist campaigns that seek to make us uniform in something so complex as how we express love. Whether queer or straight, the foundational ideology of “Black love” does not discredit myths about Black lovability so much as it validates them.

That “Black love” necessitates Blackness from both partners contradicts a core truth of Blackness in America: adding a white (or Latinx or Asian) person to the mix does not make a person less Black. Barack Obama, who grew up with his white mother in Kansas, is Black because his father is Black. He is not white because his mother is white. Bob Marley, the child of a white father and Black mother, is Black, as is his son, Damian Marley, who has a white mother. Why do we reject interracial relationships as “Black love” but accept the offspring they produce as Black people? This gymnastic racial lexicography, which embraces some Black relationships within the parameters of “Black love” while excluding others, strides uncomfortably close to the racial caste system of our grandparents’ generation, when mulatto, quadroon, and octoroon were standard ways of defining the “amount” of Blackness in a person’s bloodline.

I am not so naïve as to ignore the implicit racism inherent in the historical and present desire by some Black people to “color up,” and by others to create more racially ambiguous people through miscegenation. “Black love” strikes back against these forms of internalized and external racism. Indeed, “Black love” aspires to safeguard the purity, er, integrity of the race by promoting Black-only partnerships. But, this obsession with championing an unadulterated race doesn’t feel any more empowering or progressive because it’s coming from Black people. A more revolutionary act would be to dispose of the framework whiteness imposes altogether, and declare that a Black person’s ability to give and receive authentic, romantic love with whomever they choose is the ultimate act of self-determination—the very self-determination white supremacy attempts to rob us of daily. An evergreen expression of this phenomenon is in the schoolyard: Black kids teased—and still tease—each other for being white based on their speech, dress, and even musical interests. Let “Black love” not be a grown-up version of the self-policing we did as children. Because now, as then, we all must contend with the same racist system.

Thinking of “Black love” as a counter to white supremacist fabrications calls to mind a speech Toni Morrison gave at a public lecture at Portland State University in 1975. The most oft-quoted part of the speech is where she says: “The very serious function of racism is distraction. It keeps you from doing your work. It keeps you explaining, over and over again, your reason for being.” Deciding that a Black person who loves a white person is less revolutionary than a Black person who loves another Black person does nothing to disrupt white supremacy. Instead, it puts Black people in a perpetual state of having to prove that they are not a stereotype. Following that logic, the only way a Black person can avoid this is to date Black people. While that word “distraction” from Morrison’s speech echoes like a foghorn in my mind, the part of the speech that resonates most with me is what follows. “Be careful,” she urged the crowd, “for there is a deadly prison: the prison that is erected when one spends one’s life fighting phantoms, concentrating on myths, and explaining over and over to the conqueror your language, your lifestyle, your history, your habits.”

It’s not hyperbolic to claim that the strictures of “Black love” constitute a prison. Instead of feeling empowered to freely date who we want, Black people are told that because of racism, dating someone who isn’t Black prevents us from achieving a revolutionary love. A truly liberating antidote to the poison of white fables would declare that a Black person can love anyone and everyone they damn well please; their humanity is more than their race. Instead, “Black Love” gives us an ideology that replaces external validation for Black romance from white people with validation from Black people. White supremacy doesn’t need our help in projecting its rules and policing appropriate Blackness. If we want “Black love” to be truly revolutionary and liberatory, let’s instead insist that a single Black person’s experience of this sublime eros is enough to manifest the revolution.

Jda Gayle is a critic and boba connoisseur. She is Laid Off NYC’s Managing Editor and co-edits our Thoughts section. She lived in Crown Heights pre-pandemic but is currently based in her hometown of Kingston, Jamaica. Get to know her better: @gyaljda

*Thumbnail image: Aaron Bradshaw (@mr.blavks) and Aliyah Jones (@prophetsrevenge) at the Prospect Park Boathouse, by Raphael Helfand (@hamiltonthemixtape)