by Terrence Arjoon

The director, editor, and cinematographer Monte Hellman died last month at 91. He’s famous for Two Lane Blacktop and The Shooting: two brooding, laconic films that respectively capture the swelling tide of revolutionary malcontent in the ‘60s and its subsequent crash into the corporatization of hippie culture, government assassinations, economic oppression, and the consolidation of the American right of the ‘70s and ‘80s. In honor of Hellman’s influence on cinema, and his brave portrayal of the ennui running rampant through midcentury America, I’ve made a list of my six favorite acid westerns.

The western is integral to the history of American cinema. In 1903, Edwin S. Porter inaugurated the genre with The Great Train Robbery, in which bandits rob a train and tie a damsel in distress to the tracks. Classically, the American Film Institute defines a western as a film taking place in the American West, and concerned with the spirit, struggle, and demise of the New Frontier. The western periodically renews itself, usually during periods of national turmoil. (Consider the 3:10 to Yuma or True Grit remakes, both made during the Iraq War.) The term “acid western,” coined by critic Jonathan Rosenbaum in his review of Jim Jarmusch’s Dead Man (1995), defined it as “the fulfilment of a cherished counter-cultural dream.” But most film scholars pinpoint The Shooting as the subgenre’s first entry. Acid westerns share an irreverent surrealism, but more broadly, they embody a certain disillusionment with the New Frontier and a skepticism of its “spirit” or “struggle.”

The premise of the western is prefigured in Melville’s Moby Dick: Man, with his will, can overpower nature. The sea is the desert, and the whales massacred and painstakingly disassembled are the endless dead indigenous peoples, plants, and animals of the Americas. “I take SPACE to be the central fact to man born in America, from Folsom cave to now,” Charles Olson writes in Call me Ishmael. “I spell it large because it comes large here. Large, and without mercy.” America is the place where you can leave your family to start a new life in a new town. The place where thousands are lost in the national parks every year. The place that reduces people to consumers, alienated and distant. The American idea is contingent upon the SPACE, between here and the next frontier. SPACE can be used to justify all manner of terrible deeds and occasions, or make life bearable, or give someone an inkling of a chance at finding out who they really are.

The western is the genre, traditionally, where America tries and fails to confront its violent past. In the effort to rationalize American actions, history is twisted and blurred, and the fantasy of the cowboy arises from the repression of heinous national crimes. Cowboys—lonely, starving laborers— transform into superheroes. Indigenous peoples are framed first as hooting aggressors, then as subdued men in suits. Things become simpler. Logic escapes the mind and gets lost somewhere in Monument Valley. Trailing behind it are hordes of hungry, thirsty bodies baking in the heat.

But you can’t understate the allure of the West. The West is Freedom. Just last night I was there, flying over speed bumps through Ridgewood in my dad’s decaying luxury SUV, blasting At Folsom Prison, having just sold a set of Pipilotti Rist books to my ex-girlfriend’s friend. I felt alive, unlike myself. The road would last forever, and the lights would all be green for me.

The shape and contour of the land, and one’s movement through it, creates a fantasy space, one that distorts reality to serve ideological purposes. That’s the West: the mind ahead of the body. Basho captures this idea in his last haiku:

Falling ill on a journey, my dreams go wandering over withered fields.

Or, consider the fact that Jesus Christ was crucified on Golgotha, which in Greek was called Kranios, skull. It was in the mind that Jesus began his apostasy of the physical realm. At the limits of physical exertion, in the barren desert, the mind becomes the landscape, a space to fill.

The West is a traumatic scene America returns to, a space to flee to and flee from. It’s a site to work out the specific neuroses of the American character produced by history, agitprop, and fear. The western follows a journey in which the mind expands into the landscape, filling it with fantasy.

6 & 5. Antonioni’s The Passenger (1975) & Zabriskie Point (1970)

Americans are so poisoned by decades of indoctrination that sometimes the only way to get an accurate reading of America is through the eyes of a foreigner. When Antonioni looks at an American, he sees someone who is brash, terse, opportunistic and short-sighted. (He sees this in most Italians as well, but the observation still holds.) We are confronted with the mystery of the face, how blank it is, how hard it is to know what someone is thinking, or why they do things. In The Passenger, Jack Nicholson’s Locke, a journalist, seizes upon his new acquaintance Robertson’s death in a hotel room in Chad as a chance to fake his own demise and take over Robertson’s life. The American identity is looser than most, and the urge to begin again, which is really a disguised death drive, rises up when the opportunity presents itself. Locke (now Robertson) quickly finds out that the man whose identity he’s assumed was a gunrunner, perhaps for the very militias he was reporting on. He feels compelled to keep Robertson’s appointments, traveling across western Europe to Seville. The landscapes are vast, and empty: Where an American goes, he brings his emptiness to fill the space. When you see Nicholson’s smile, or the ease with which his character abandons his career and family, you are reminded of the violence in the American face. The smile is there as a warning and a deflection: “Don’t get in my way, for my teeth are bright and sharp.”

Then there is the critically reviled Zabriskie Point. Perhaps Antonioni looks too honestly at the revolutionary shortcomings of the New Left’s focus on electoral politics. Perhaps, as critics say, the story is too meandering in the middle. Perhaps the actors are terrible (they are). The narrative begins with Mark storming out of a student activist meeting, being arrested at a protest, and buying a gun with a friend. Mark goes to a second protest where he considers shooting a cop. Failing to do so, he steals an airplane. We are introduced to Daria, a real estate agent’s assistant on her way to her boss’s Modernist property in the middle of the desert. There is a twenty-minute sequence in which Mark hazes Daria, circling and dive-bombing, nearly hitting her, as Daria’s interest in him is gradually piqued. The viewer is confused: How long will this scene go on? They’re both beautiful and young, so we want them to get together, but is that such a good idea? When they meet and have sex in Death Valley, kicking up sand which floats in the air like ash, dozens of other hippies populate the crevasses, making love. It looks like butoh.

Antonioni uses non-actors to great effect. Mark Frechette lived on a commune; Daria Halpern was a dance therapist. They’re American, but watching the movie I assumed they were Italians speaking rehearsed syllabic english. Their actions are incomprehensible. Upon witnessing a cop shoot an unarmed Black man, he expresses horror—not over the innocent protestor’s death, but over the fact that he was too afraid to shoot the cop. Fear, anger, and lust boil over inside him. His only moment of freedom is in the stolen plane over the desert.

Antonioni, however, rejects the dichotomy of City vs. Wilderness. Mark and Daria are just as lost in the desert as they were in society, but in Death Valley they have room to act out their desires and fears. The West serves as a playground for their hippie fantasy of free love and the glory of the open road. When they return to their lives, the fantasy is brutally extinguished. Mark is murdered and Daria languishes, impotently dreaming of blowing up her boss’s property. Their journey is a memory, a dream of a failed future that never came.

4. Jia Zhangke’s Ash is Purest White (2019)

Bing (Liao Fan) and Qiao (Zhao Tao) are classic gangster and femme fatale archetypes in a failing former industrial town. They dance all night to American music but know the fun will end someday. Qiao is madly in love with Bing, who seems indifferent to her. She sacrifices her freedom by using an illegal gun to rescue him from a rival gang’s attack and spends four years in prison for the crime. She expects, and is perhaps rightly owed, fealty from Bing for her sacrifice. But when she is released, her China is different, and she is alone.

Qiao is unmoored from her previous life, adrift in a vast and lonely country pitted with huge land projects, massive developments, and poor, desperate people. Men try to take advantage of her, but she skillfully uses their malintentions against them. She fools gamblers at a casino into thinking their wives know about their mistresses to steal their chips and food. She tricks a horny delivery guy into driving her to Bing’s house. The only people to get the best of her are a woman who steals her bag on a ferry, and Bing. He dodges her several times and rejects her when she finally confronts him. Years later, weak and sickly, he reaches out to her. She nurses him back to health. When he can walk again, he abandons her.

I give the full plot here to show how simple it is, and how wide the divide is between content and presentation. The first part of the film takes place in Datong in 2001, the same town and year as Zhangke’s Unknown Pleasures. It plays like a wuxia gangster flick until Qiao’s sacrifice and the government’s realistic response shatter the archetype of the lone hero fighting for honor against an unjust bureaucracy. The middle section of the film takes place in 2006, set at the time of Zhangke’s Still Life. Zhao Tao, now playing a different character, rides a ferry down the same river she did in the earlier movie. Zhangke films in real-world locations, and the Three Gorges Dam project has since flooded the town that previously existed there. In the final segment of the film, Qiao travels back to a cold and alien Datong. Development is rendered as a surreal project with no discernable goal but the accumulation of capital by the elite. All of China is a New Frontier of endless growth and decay.

When a nation develops, what is it running to or away from? Itself? Zhao Tao—Zhangke’s wife and longest collaborator—inhabits old roles and old selves, switching effortlessly and endlessly. What do you do when you outlive your usefulness? Bing wants Qiao to be disposable and is made uncomfortable by her devotion. How can you tamp down soul-tarnishing love, and why should you?

3. John Gianvito’s Profit Motive and the Whispering Wind (2007)

There are no human characters in Gianvito’s hour-long documentary; only historical markers that dot the American landscape, situating the sites of massacres, strikes and failed revolutions. They recede into the wild grass growing around them, and the rocks where they are mounted threaten to absorb them whole. Like half-hearted apologies or glib texts to someone you have hurt, these monuments ultimately mean nothing. Gianvito interpolates still shots of the markers with footage of grass and trees swaying in the wind and hand-drawn images of people harvesting grain. When one reads a description of a failed slave rebellion and then sees hundreds of blades of grass moving in unison, one feels an unsettling sense of peace. As in a Malick film, nature’s quietude and beauty makes up for human—or, more specifically, American—denialism. We jog past the markers of our collective shame every day and build Exxon’s across the street from them. And all the while the past threatens to break forth and drown us all.

2 & 1. Hellman’s The Shooting (1966) & Two-Lane Blacktop (1971)

The Shooting concentrates the power of the western into something strange and, dare I say, Kafkaesque. In the same way The Trial is concerned with the anti-human and meaningless bureaucratic procedures of establishments, The Shooting is concerned with the rules of the West: When there is a damsel, you must pick her up. When there is a rider arrayed in black, you must be afraid. When the sun beats down on you, you must be tired. Most importantly, you must seek revenge. Hellman places the traditional archetypes of the western in a world that doesn’t reward them in the traditional way. 1966 was the year LBJ reinforced and amplified American involvement in Southeast Asia; the year Ken Kesey began his Acid Tests; the year of wildcat strikes and race riots; the year of the mass shooter. Nothing was as it seemed.

Gashade (Warren Oates) is a former bounty hunter who now runs a mining camp with his brother Coigne, his lackey Coley, and Leland, whose death initiates the events of the film. Coigne has fled, and Coley is terrified. The mining camp is situated in a pit ringed like Dante’s hell. The atmosphere is oppressive. A mysterious woman shoots her horse dead outside of camp and offers the men payment for assisting her in her journey to a nearby town. Gashade suspects she is after Coigne, who went missing the previous evening. Gaschade, Coley, and the woman leave the camp, followed by Jack Nicholson’s Man in Black.

Gashade gradually realizes the trio is being followed, and that the woman’s erratic actions are messages to the Man in Black. No one trusts anyone. There is no witty banter or heroism; only the sad reality of the sun, the flies, and death. They journey to what feels like the end of the world. With motive obfuscated, the journey itself assumes meaning.

Two-Lane Blacktop holds a dark mirror to Easy Rider and The Shooting. Easy Rider mythologizes its characters: They are “different” because they ride motorcycles and do drugs, and they are punished accordingly. But the men in Two Lane Blacktop—the Driver and the Mechanic—are losers. They travel in a souped-up ‘50s Chevy across a quickly modernizing America, challenging other drivers to race them. They don’t say it—in fact, they say almost nothing—but we know why they do it: because the road is there, and because there’s nothing else to do.

The two-lane blacktop is the ultimate example of the New Frontier’s virtue: By laying down millions of miles of hot, stinking tar and painting two straight yellow lines in the middle, we tamped down the unruliness of the land. Endless roads, overpasses, highways, and traffic cops, bind the country into a stress position. They make everywhere easy to access and make every place the same. For the Mechanic and the Driver, riding the open road with no purpose subverts its intention, turning a product of civil engineering into an instrument for aimless pleasure.

Warren Oates (of The Shooting) stars as GTO, a vain and insecure man who challenges the Driver and Mechanic to a country-wide race. He is desperate to be liked, and changes his personality to suit whomever he talks to. For company, he picks up hitchhikers, including a businessman, a gay drifter, and two soldiers. He wears a new neon cashmere v-neck sweater in every scene. His chameleonic nature contrasts with the monotonous presentation of the Driver and Mechanic, who show no emotions other than anger, sadness, and the thrill of the road.

The Driver and the Mechanic are played by James Taylor and Dennis Wilson, two of the ‘60s’ most famous musicians, but there’s no music here. Their silence is deafening. They grow to pity GTO and eventually form an alliance with him. They pick up a hitchhiking woman, The Girl, who eventually grows tired of the group and abandons them in a diner parking lot. By the end of the movie, everyone has lost steam. GTO picks up two new hitchhikers and departs. The Driver and Mechanic begin a new drag race to get some cash, and the film runs out. In a land without meaning or hope, there is no end.

Audiences stormed out of the theater. According to the laws of old Hollywood, we are owed narrative satisfaction. Without it, the story lumps in our stomachs. If the acid western is a reality in which the New Frontier has been subsumed into the texture of everyday life and rendered meaningless, Two-Lane Blacktop pares the genre to its bare necessities: There is SPACE. It was conquered by your ancestors and filled with death and bones, and you are trapped in it.

Terrence Arjoon is a poet and educator living in Brooklyn. His latest poetry collection is 36 Dreams from 1080 Press. You can find more of his work at his website. Get to know him better: @terrencearjoon

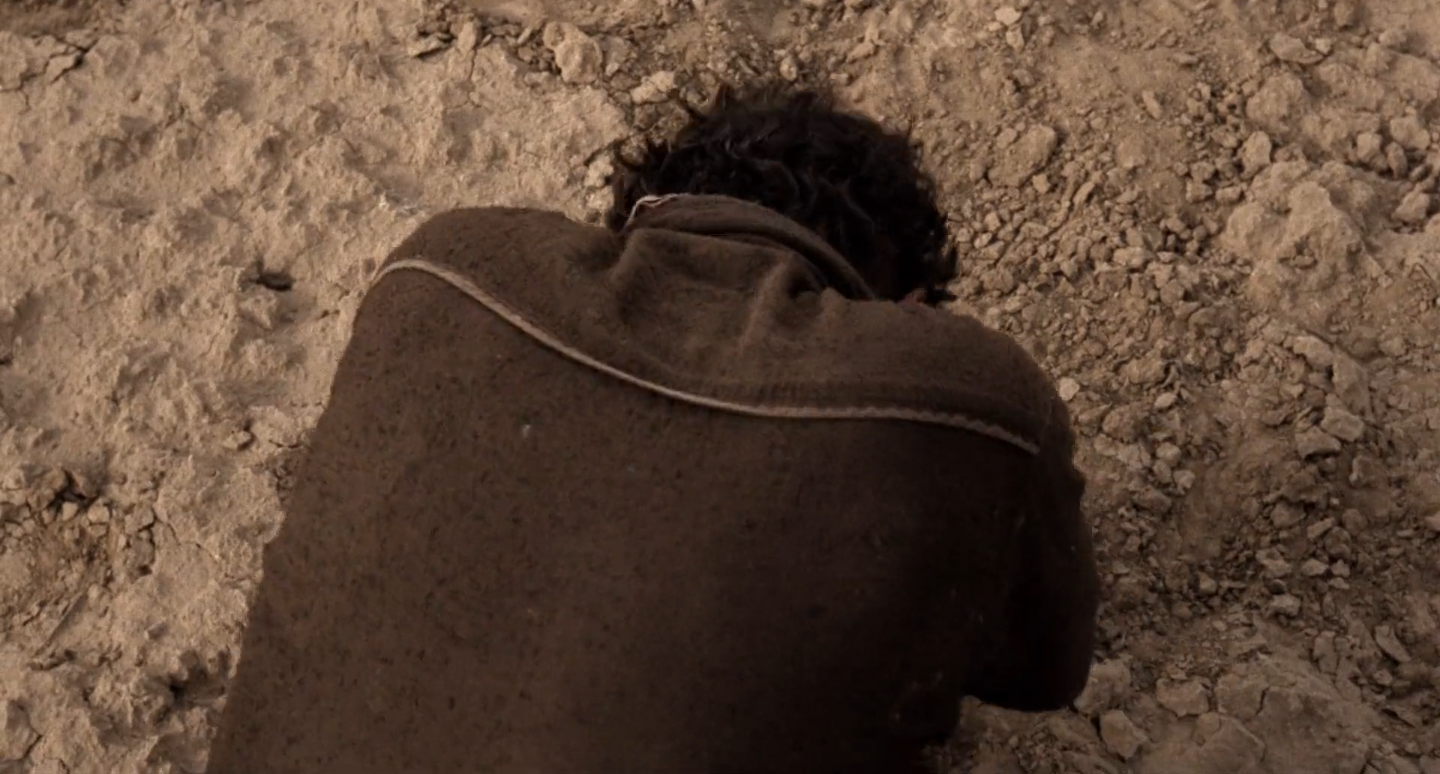

*Thumbnail image: Still from Two-Lane Blacktop