by David Kobe

I like the feeling of pressing my forehead against a cold hotel room window. The higher up you are, the colder the window feels. If you are stressed or uncertain it feels particularly good. There wasn’t much room to pace in the hotel room, and while I watched the riot on Capitol Hill, that’s all I felt like doing. Peering out of the 20th-floor window of the boutique hotel NOMO SOHO would have to suffice. The aimless decor, white walls, and mirrored partitions created an unnerving environment for ingesting the news coming from our nation’s capital.

Watching the storming, I noted different characters. Jacob Anthony Chansley, the QAnon shaman, wore a coonskin cap with horns. Eric Munchel, the man who bounded across the House galleries with flex cuffs in his hand, wore tactical gear and reinforced gloves. Aaron Motofksy, who was photographed taking a rest on a bench in the Capitol, wore furs and was equipped with a staff and police shield. He looked like a confused non-playable character in some shitty role-playing game, stuck in a glitch.

For two years, I worked in Washington, D.C. for a certain conservative national news channel. Most of the time I was in the bureau on North Capitol Street, but occasionally I assisted a roving crew in the Capitol Complex. Every once in a while, a video comes up on Twitter of a group of Capitol Hill reporters, producers, and on-air talent shuffling backward while a Senator walks to the Capitol Hill subway system that runs between the office buildings and the Capitol. For a little while, that was me. I was on the hill for hearings with Carter Page during the infancy of Russiagate, cornered Sen. Lindsay Graham with a slew of reporters during the 2018 government shutdown, and asked Nancy Pelosi if she was worried about a challenger for Speaker of the House when the Democrats retook it in 2018. I lived in a Columbia Heights row house with a cadre of consultants and hill staffers. I had a college friend who worked for a Republican senator. There were awkward lunches in the Capitol Hill cafeteria with reporters from the Daily Caller. I’d get a hummus plate—the plastic ones you find at airports—and a red-eye.

So when I saw the Capitol under siege by rioters, it felt surreal, but not because it was hallowed ground. For me and so many others, it was a mundane workplace. The complete idiocy of the Trump administration mixed with my own professional malaise left me disenchanted. I laughed seeing rioters keep within the rope lines like they were being guided on a tour led by an intern from their congressional office. The rioters, at least the most extreme among them, saw Capitol Hill as a symbol of the pedophilic deep state. Those more tied to reality saw it simply as the center of liberal corruption.

Capitol Hill is a beacon of democracy to the world, and there are many people there who are earnestly working to make the country a better place. But from my perch in my corner of conservative media, Capitol Hill seemed like a nursing home staffed by uninspired 22-year-olds in Bonobos queuing up to work on K Street. As deadly serious as this attack was, I had a hard time squaring the dramatic language coming from pundits with the images I saw from my hotel in real time.

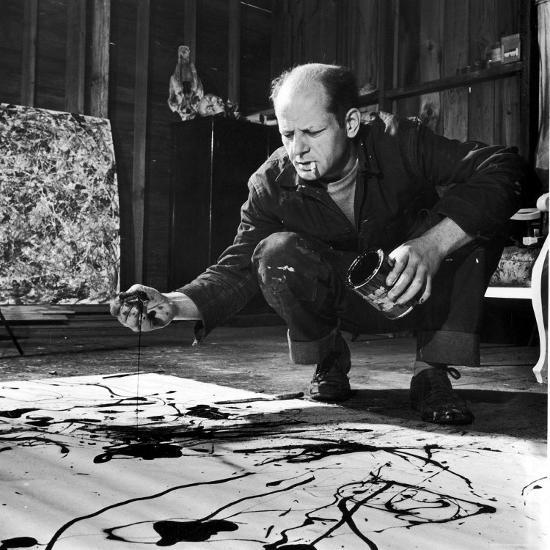

It’s difficult to hold the two truths of this riot in your mind. It was at once a vicious assault on American democracy and a pathetic reddit meetup, a revolutionary live-action role-play that seemed more focused on scoring points online than actually achieving its insurrectionary goals. Folks on the ground ranged from MAGA rally wooks to militia-style combatants with military experience. Their actions ranged from occupying the Capitol lawn and taking selfies for Facebook, to assaulting a Capital Police officer with a fire extinguisher. Twitter user @elisethoma5 said it best: “For me, the striking thing about so many of these images of rioters in the Capitol is that what they’re doing—all of them—is creating content for social media. At least in their minds, the true seat of power is not actually in that building. It’s online.”

From my hotel room I watched a Twitch multicam stream that showed body camera POVs from both inside and outside the Capitol. One streamer directed all the coverage from his room, which had its own frame. His setup was similar to those of most gamers on Twitch: ergonomic chair, gaming headset over his ears. His eyes darted between feeds, making sure he wasn’t missing anything. It reminded me of sitting at my old desk, monitoring my email and the AP newswire.

On the stream, other windows showed American flags crashing through doors, Capitol Police forming human barricades, and protestors wandering the lawn like festival-goers. I started to panic—How violent could this get? My girlfriend and I decided to go on a walk. On our way out the door I saw a girl posing in front of a half-finished mural of Angela Davis in the lobby while her boyfriend snapped photos.

In the lead-up to 9/11, our culture had taken a turn towards destructive pessimism Popular movies of the 1990s had a particular fetish for the kind of destruction that would mirror the September 11th attacks. Filmmaker Adam Curtis makes this point in his 2016 film Hypernormalisation, while a montage of scenes from pre-9/11 films such as Armageddon and Independence Day show destruction on a massive scale. Throughout the Obama era, films like Olympus Has Fallen and White House Down (both released in 2013) reflected the same kind of pessimism, this time aimed at Capitol Hill. The idea of a violent siege on Washington grossed $375 million at the box office that year. So when I watched the Capitol Hill riot play out on television, it felt like a newsreel from a B-movie I had already seen. Our dreams of destruction were coming to fruition yet again.

The immersiveness of first-person shooters feed our self-destructive impulses even more explicitly. In “The Battle of Washington,” a mission from 2009’s Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2, you follow a platoon as it weaves through a decimated DC, fighting invading Russian forces. Tanks roll past as you march down Pennsylvania Avenue. Senate office buildings smolder in the background. You battle through the Eisenhower Executive Office Building and rush to the top of the White House to stop the American Airforce from bombing the building. From there, you take in a grand spectacle: Smoke covers the skies above the National Mall. Buildings are engulfed in flames all the way to the Potomac River. A chunk is taken out of the center of the Washington Monument.

It’s a QAnon fever dream. The district is obliterated and you, the player and the hero, are tasked with saving it. If you harbor resentment toward the United States you can live through the obliteration of the nation’s capital. If you fancy yourself a patriot, congrats, you just saved the White House. Modern Warfare’s genius is that it scratches both itches. It allows us to indulge our appetite for insurrection and lets us single-handedly save the country, all at once.

There is a playthrough of “The Battle of Washington” on YouTube. “So is anyone here because of current events?” a commenter wrote after the riot. “Who’s here after the capitol building was stormed?” another asked. “Only a matter of time before this is reality. Not from Russia though, from our own people. Yesterday was just a taste of the second civil war coming,” said another. “This is how Washington DC is gonna look like by February” got 619 thumbs up.

The images coming from the Capitol were so strange to behold because of their uncanny resemblance to the virtual world. The costumed protestors who breached the Capitol Building could be characters in any number of first-person shooter games—survivors of a nuclear holocaust in a white nationalist installment of the Fallout series, or Fortnite players in special edition insurrectionist skins.

Our country’s enemies caught wind of our culture’s self-destructive obsession and reappropriated it for their own strategic purposes long ago. The authors of “Call of Duty: Jihad—How the Video Game Motif Has Migrated Downstream from Islamic State Propaganda Videos” describe how downstream ISIS organizations' create sleek trailers for online recruitment that mimic first-person shooters. The aesthetic mimicry is meant to endear the videos to young people and attract them to the cause.

But this aesthetic imitation is not limited to foreign terrorists organizations. The U.S. Army imitates first-person shooter games in their advertisements, and in 2018 they founded an Esports team that actively recruits at gaming conventions. Twitch had to step in when the army started using fake giveaways to direct players to its recruitment webpages.

What is potentially more alarming than the brazen attempts by the U.S. Army to use video games tropes to target recruits is the way in which members of Congress co-opt the violent first-person shooters imagery and then back away from the consequences of their messaging. In December, Rep. Dan Crenshaw (R-TX) put out “Georgia Reloaded,” a piece of content that is difficult to describe. It’s a Republican hype video for the Georgia Senate race, somewhere between an ad, a trailer, and a propaganda film. In the video, Crenshaw delivers a patriotic speech about America and is subsequently briefed on “the far left threat.” A montage of Democratic boogiemen plays, and Crenshaw is deployed in Georgia to help Sen. Loeffler and Sen. Purdue win the upcoming run-off. We see him jump from a cargo plane and intercept a group of Antifa infantry. He punches out their windshield as suspenseful music plays. It looks like a terrible first-person shooter cut scene. Crenshaw, with his signature eye patch, looks like Solid Snake from Metal Gear Solid. There are explicitly violent connotations in the video if you can look past its cheap virtual kitsch. Behind the kitschy visual effects inspired by action movies and first-person shooters is an insidious call for violence against political enemies of the right. It’s silly, and that is precisely why it's dangerous. Like the Capitol Riot itself, it's initially difficult to understand how seriously to take the violent messages.

In The Toxic Meritocracy of Video Games: Why Gaming Culture Is the Worst, Christopher A. Paul asserts that games “are a product of assemblage and co-creativity... the belief that media products are constructed in the interactions between producers and consumers of content.” He elaborates on why games are difficult to categorize: “Part of the reason why games cannot be isolated into neatly compartmentalized parts is that the co-creative relationship of players and producers of games is crucial to their production.”

The degree to which Crenshaw’s ad mirrors the videos produced by minor league ISIS wannabes is striking. In downstream ISIS propaganda videos inspired by first-person shooters, enemies are shot from afar. Their messaging is rarely as bloody as the actual acts of terrorism they commit. Their potential recruits are numb to the implication. But at least—unlike in Crenshaw’s ad—the dichotomy between producer and consumer is clear. In ISIS videos the direction of influence is linear, top-down. In the instance of Crenshaw, this dynamic is not so obvious.

Crenshaw is both producing and consuming right-wing media, as are his supporters. They interact on the internet, exchanging and producing content like any online fan community would. This unrelenting, decentralized feedback loop is what makes the right-wing movement in the United States so powerful. The kind of content that Crenshaw makes “cannot be isolated into neatly compartmentalized parts,” as Paul says, because it situates itself in a co-creative position. It’s hard to tell if Crenshaw is a developer or Player One. What is so dangerous about his co-creative role is that when violence erupts, as it did weeks ago, it's difficult to lay the blame at his feet. Crenshaw and his Republican colleagues can refuse to acknowledge any responsibility and find themselves with enough plausible deniability to skate by.

If we see the attack on Capitol Hill— the entire Trump administration, even—as one sweeping media product, a LARP on a national scale, Paul’s assessment makes a lot of sense. This era of politics has been so difficult to parse because it has had such a large and insane co-creative community. The developers of Trumpist politics (Trump himself, Steve Bannon, Stephen Miller) mingle with the players: the far-right enablers (Crenshaw, Ted Cruz, Josh Hawley) and the QAnon conspiracy theorists who form their base. It is a strange interactive experience. Fact and perception melt together Until recently, those receiving and repeating our most destructive cultural messages have lived mostly online. But now the most nefarious segments of the alt-right have migrated from the virtual to the tangible

When I moved to Washington D.C. in 2017, the online world still felt separate from Capitol Hill. Republican Senators insisted they did not read the President’s tweets. The gap between the dark corners of the internet and the halls of Congress still felt vast. The cultural psychology of the last decade had not caught up to lawmakers yet.

Those who witnessed the Capitol Hill riot briefly saw the convergence of these online and offline worlds. The trolls were knocking on the gates and they were heavily armed. It’s difficult to know if the events of two weeks ago were the final boss or simply a tutorial.

David Kobe co-edits Laid Off NYC's Politics section. Get to know him better: @david_kobe