by Raphael Helfand

Naeem Juwan is reborn. From the ashes of Spank Rock, the raunchy rapper who helped put Baltimore club on the map 15 years ago, Naeem has risen. Startisha, his debut album under the new moniker, is out now via 37d03d.

Returning to his given name is only the most superficial change Juwan has made in the six years since the last Spank Rock project. The real transformation is in the music. Where Spank Rock was lewd and immature, Naeem is meditative. Spank Rock’s lightning bars are less ubiquitous, largely replaced by refreshingly raw singing, a strained falsetto somewhere between a less affected Sean Bowie and a less trained Dev Hynes. Production-wise, he’s traded in the 130bpm beats of his boyhood for slower, more harmonic production from Grave Goods and Sam Green, and found unlikely collaborators in Ryan Olson and Justin Vernon’s Gayngs collective, which he got to know while he was recording the new album in Minneapolis.

Juwan lives in L.A. now, and while he’s spiritually proud of everything the Black Lives Matter movement has accomplished there, his corporeal form hasn’t been out on the freeways with the rioters. He’s been sheltering in place, isolated from the protests by the city’s sprawl.

I spoke with Juwan on the eve of Startisha’s release. We talked about his Bmore club origins, writing stoned, and the politics of personal protest music.

NAEEM: Are you from Baltimore?

Raphael: No, I’m from New York. But I have a lot of questions about Baltimore. I don’t know a ton about Baltimore club or Baltimore hip-hop, but I know you came of age in the club scene. What was that like?

I grew up with Baltimore club music all around me. It was the music we always listened to growing up. So when I was working on the first [Spank Rock] project, we started incorporating a lot of Baltimore club sounds. But we were making the music in Brooklyn and doing a lot of shows in Philly. We played in Baltimore too, but it was wild to be a part of that first wave of musicians that was spreading club music to the rest of the country and the world. It was funny hearing something that was so local all of a sudden being recognized by New Yorkers.

Like all the club and dance scenes around the country, Baltimore club music started with queer people of color. A lot of those scenes—New Orleans bounce, Chicago house, Detroit techno, DC go-go, Miami jook, etc.—started similarly, but have all been coöpted to varying degrees by mainstream white capitalist culture. Do you feel like that’s happened with Baltimore club too?

My understanding of the Baltimore club scene was that it was a very diverse group of people. Miss Tony was a big star in the Baltimore club scene, and she would dress in drag. But the label she was putting out music on wasn’t necessarily a queer label. And even though Miss Tony was known as gay or a drag queen or whatever, the city didn’t really split it apart that way. We wouldn’t be listening to Baltimore club music thinking it was part of the queer scene, more just the Baltimore scene.

It was interesting how it was coöpted. Philly was listening to a lot more Baltimore club than I knew when I got there, so it was also part of their culture. And that turned into Philly club, and you had people like DJ Sega making club music. And then it worked its way up to Jersey. I’m not sure how early Jersey had Baltimore club or was influenced by the scene, but it was really interesting how the media started changing the term from Baltimore club to Jersey club. So that’s coöpting in a way.

But also, people like Diplo would rip off Blaqstarr’s beats. And it became popular for indie kids to make Baltimore club remixes or for EDM kids to incorporate those sounds into their production. But that’s nothing new. That’s just the way the industry treats the people who created the music. It’s so fucked up that the inventors of it, the people who made the best versions of it, who are still alive, have fallen out of the spotlight. But there’s always time to change that.

From what I understand, Baltimore hip-hop, unlike club, has split into two scenes—the street scene and the hipster scene—in the past decade. At least that’s how I’ve seen it categorized by critics like Lawrence Burney. When you were Spank Rock, the media put you on the hipster side of that divide. Do you still feel like you’re part of that downtown Baltimore hipster scene?

Yeah, I’ve always felt like that. The thing about being creative and trying to make something that doesn’t already exist in the world is that, often, the scene that’s most welcoming to you is that art scene. So though people try to spin the word hipster and make it a negative term, those are the people in your city who are the most forward-thinking. Those are the radical people in your city. So being a part of the radical scene in Baltimore, there was a great mix of graffiti artists and punk kids and fine arts students. That was a place where I had a home for my music, because it wasn’t accepted other places. When I first started making albums, Baltimore hip-hop probably sounded closer to neosoul. Maybe there were some movements bringing Baltimore club breaks into the music, but it was all so downtempo. What I was doing was very uppace. There wasn’t a scene for it at all. Also, I was living in Philly during that time. So being a part of the art scene, not just in Baltimore but in Philadelphia, and being able to travel between Bmore, Philly and New York and create this tristate kind of feeling was really important for me.

A lot of people compare those early Spank Rock records to 2 Live Crew. Were they a big part of your musical development?

Yeah. All the Baltimore club songs were really raunchy, so 2 Live Crew fit into that. Snoop’s Doggystyle album was a big influence for me too. But I was also very influenced by Black Star (Mos Def and [Talib] Kweli) and Wu-Tang. So though I was making very fast-paced club music, I tried to make sure that lyricism was still a part of it.

Black Star had some Baltimore production, right?

Yeah, there’s a really amazing producer by the name of Ge-ology that had some production credits on the early Black Star albums. He was a big influence on me as well. Knowing him in high school and getting to see him DJ, he taught me a lot about hip-hop when I was very young, before I ever tried to make it in music.

Back to 2 Live Crew, can you talk a little about Uncle Luke’s Baltimore connection?

I think so. I got a chance to talk to Luke for this Fader issue I was part of. It was around the time that me and Benny Blanco put out Bangers & Cash, where the whole EP was dedicated to 2 Live Crew and we sampled a bunch of their songs. It’s been such a long time since we did that interview. But if I remember correctly, Luke was talking about Miami bass music not being accepted as part of hip-hop in New York, but being accepted in Baltimore. Baltimore was a place that he always loved.

It’s been six years since the last Spank Rock album, and now you’re coming back under your given name with a much rawer sound. What have you been up to all this time?

Um, I’ve been… I don’t know. [Laughs] When you say six years, it doesn’t really register to me. I can’t even remember back that far. I was working on music in Philly. I spent a lot of time dedicating myself to meeting new people in the Philly music scene and trying to keep up with a lot of the artists there for the making of this album. Meeting Grave Goods and Sam Green was the biggest part of my past six years, forming a creative working relationship with them; keeping up with people like DJ Haram, Moor Mother, Noah Breakfast; really paying attention to the new wave of musicians there. That’s what I’ve been doing the past six years, and slowly writing songs for this album.

I saw you said in an interview that you let your Sam (Green) and Zach (Grave Goods) do their thing, completely separate from your process. I was wondering how that worked exactly.

It wasn’t separate from the process. But I had started becoming more demanding about what I wanted production to sound like, and I was offering a lot more ideas on some of the later Spank Rock projects. And for this one, I wanted to let go of that desire, that wanting. I wanted to focus on my feelings and how I responded to things. I knew that the things that Sam and Zach were gonna make were gonna be perfect for me as a songwriter. So I would show up to the studio, and whatever they were making, and however I’d respond, that’s what went on the track. It was a way more organic feeling than being like, “I wanna do a bounce song,” or, “I’ve gotta do a Baltimore club song.” I didn’t step in the studio with those ideas of how to make an album for it to be consumed by the public. I wanted to make a time capsule of my emotions, and Sam and Zach’s emotions.

So the songs generally started with production, and then you’d write something on top?

Yeah. I would just show up to whoever’s spot we were working at that day, and I’d sit there and see what happened. Sometimes something happened. Sometimes it didn’t. Sam was living in west Philly, and I was in south Philly. And sometimes, after the session, I would walk back home, which probably took about an hour and a half, and I would think to myself about what we worked on and come up with ideas. It was meditative.

There are still club sounds on the album, but you’ve also pulled in all these new outside influences. How did you get involved with Justin Vernon and Gayngs? What spoke to you about that sonic world they’re in?

Ryan Olson from Gayngs and Poliça was at the first Spank Rock show I did in Minneapolis. And then he started inviting me out there. He wanted to bring me into his world, and I formed a friendship with him. And when I was there finishing this album, he had some interest in helping me put the icing on the cake. So I got introduced to the whole crew, including Justin [Vernon], Velvet Negroni, Francis and the Lights. It came together naturally. It wasn’t like I was seeking out working with Justin or Ryan. It was just where the music led.

You’ve also adopted a whole new vocal style. Is there anyone you’re trying to emulate?

My favorite artist of all time is Prince. I love Prince so much. But I’m not that good of a singer, so when I was writing this album, I was listening to a lot of different singer-songwriters that had more unique voices—Prince’s voice is unique, but he can hit those notes pretty cleanly. And so to give myself confidence, I started listening to people like Robert Wyatt and Leonard Cohen to understand the importance of having your own unique voice, how impactful that can be.

I wouldn’t have guessed Leonard Cohen. He sings in a very different register.

[Laughs] Yeah, it’s totally different. He never does the falsetto trip. But he’s someone who started off as a poet, who wasn’t super comfortable with singing, and turned into a singer. His voice still grips you. It’s still very powerful. So I used those examples to try to feel more confident and figure out my voice.

That Prince-inspired falsetto jumps out immediately on the first track, “You and I,” which, by the way, I think is better than the original, and I love Silver Apples. Why’d you decide to open with a cover, and how did you come to fully reinterpret it the way you did?

I wanted to cover that song for a really long time. I remember being in London and floating the idea to Mark Ronson. I thought I was gonna be able to convince Mark to have me, him and Beth Ditto do a cover of the song. I wanted to sing it as a duet. That never happened. I’m a terrible singer, so…

Not true!

Well, I’ve gotten a little better. But back then, Mark probably looked at me like an idiot. But that song really struck me. It’s such a beautiful socialist love song, and I thought it was a really important message for people today. I love hearing people cover other people’s songs. I love Isaac Hayes’s covers and Nina Simone’s covers. So I was really into the creative challenge of turning this song into a totally different thing, something that was almost unrecognizable. But the spirit of the lyrics was really important to me.

Next up on the album is “Simulation,” which feels like a bona fide 2020 hit. It’s got that nice intro that reminds me of the Aphex Twin sample on “Blame Game.” Did y’all have that in mind when you were making it?

“Simulation” is an interesting one because it was one of the last songs I wrote for the album. I had pretty much the whole album written in Philly with Sam and Zach. I was coming back from tour and wanted to work on some music with my friend P. Morris. So I flew to Kansas City from Australia and wrote this song with P. Morris and Tom Richman. And then, when I got back to Minneapolis to finish the record with Sam and Zach and keep hacking away at it with Ryan, Justin was listening to it. He had this weird little voice sample, and he started playing piano over the top of the beat, and that’s when it snapped into place.

The lyrics on that track get pretty intense. I love the line, “This ain’t rock ‘n’ roll, this is patricide,” but I’m not sure I get it. What does it mean to you?

It’s a reference to a David Bowie lyric. He says, “This ain’t rock ‘n’ roll, this is genocide.” When I heard him say that such a long time ago, I could never let that go. It was so impactful, and I wanted to do an updated version of that. I say patricide instead of genocide because we really have some work to do in killing the ideology of our fathers. The way masculinity has played out around the world has been devastating to the earth and devastating to a lot of people—women and the LGBT community and men themselves.

“Woo Woo Woo” feels like a posse cut, even though it’s just three of you. It’s definitely the track on the album that sticks out as dissonant with the rest of it. Was it your way of signaling that you’re still Spank Rock in some way, still the same Baltimore rapper you’ve always been?

Everything I did on this album is not about signaling.

Bad word choice. Sorry.

No, it’s OK. As I was making the album, I wasn’t considering the audience. I dedicated my process to Sam and Zach, and myself and my feelings, and what was happening immediately, right there in the room. When Sam and Zach made the beat, I had smoked too much weed. I don’t smoke weed very often, and I smoked too much and fell asleep in the studio. But I had a rule where I didn’t leave the session without writing something or trying something out. So when I woke back up, I started mumbling to myself, and I wrote the first verse and threw it down before I left. And then Amanda [Blank] heard it, and she was like, “Yo, I’m tryna get on this. This shit’s crazy. Let’s put Micah [James] on it too.” I think the coolest thing about the way the song turned out is that it is like a posse cut. We didn’t want to focus on hooks. It reminds me of Digable Planets, or a Native Tongues posse cut with Monie Love, Queen Latifa and Busta. I never made anything like that. I’m usually doing songs with no features or collaborations. So it was really fun to have extra voices on it.

I know you’ve already told the story of the title track, but I think it’s a great story, and I don’t want to paraphrase it here. Can you briefly tell it again?

Startisha was a friend of my sister Maya, who’s two years younger than me. She had so much energy; she was pretty wild. It was always fun when she hung out on our porch. One day we were having a family party at the house, and some Baltimore club came on, and Startisha started dancing on me. It was this really funny, embarrassing moment, as a 13-year-old boy in front of his parents. Like I said, the practice of writing this album was sitting and thinking about whatever my mind was holding onto, and that memory popped into my head. And you know how memories are. They can be completely false. Maybe that never happened. But I remember this moment, and I thought it was so interesting that someone from my childhood, who I haven’t seen or spoken to since, made such a big impact on my life.

I started thinking about friendships and how they make us who we are. I wanted to dedicate something to those people in our lives who aren’t the role models. We always focus on these iconic role models. Like, Prince changed my life. But also, this one girl who is not Prince, who is not Obama… [Laughs] I still remember that, and I still hold onto her life dearly. I wanted to put her name in lights. A name like Startisha, people don’t make songs about it. You can’t buy that name in a gift shop, just like you can’t buy Naeem. It was really important to me to create a mantra out of my memory of her.

“Us” and “Stone Harbor” make a really cute double love song in the middle of the album. What or who are you most in love with right now?

Man, that’s a hard question. [Long pause, laughs] I’m trying to think of a good answer. I’ve been with my boyfriend for over 11 years, so that’s the obvious answer. But I think I’m really in love with the creative process, and how impactful it can be. I’m really enjoying making things lately, whether it’s making the “Simulation” video with my boyfriend Scott, or writing music for the next album. For a while, I wasn’t in love with the process at all, so it’s nice to feel good about it again.

“Tiger Song” feels like the only truly political track on the album, and it comes right at the end. Right now feels like a perfect time for that song to come out, because it makes a statement about militant resistance to oppression. In light of everything going on, what can we take from that song to use in the streets when we protest?

“Tiger Song” is a tough one. It was me wrestling with my own identity. It wasn’t meant to be a political song, even though I bookend it with Malcolm X and Martin Luther King. I start the song off by saying Malcolm was a failure, which is a really controversial line. And then I end the song comparing Martin Luther King to a farmer. And I also begin the song by saying I was born with three seeds in my palm, hinting that maybe I’m a farmer as well, a farmer more than a soldier.

The song itself is me dealing with a lot of pain that I held onto, trying to live up to some idea of black masculinity. I’m glad it reads as a political song, because it is, in a way. There’s a lot to decipher in this world. You’re born and you don’t know where you’re gonna land at. You don’t know what family you’re gonna be born into. You don’t know what diseases you’re gonna have. You don’t know what color your eyes are gonna be. And you have to make your way through life being completely surprised.

I hope that the people do read it as a political song and understand that it was an act of questioning everything around me, not an act of making an argument for something. You ask as many questions as you can until you get to the truth.

Get to know Raphael better: @raphaelhelfand

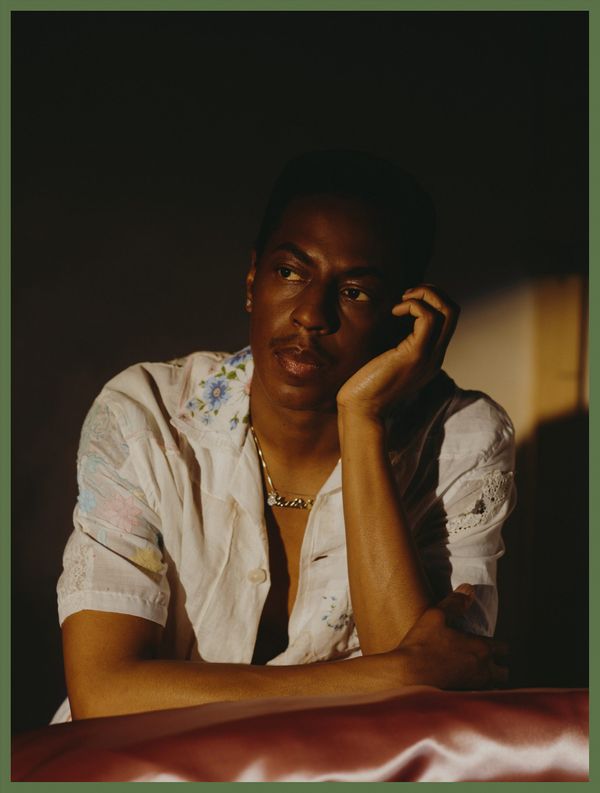

*Thumbnail Image by Shane McCauley