by Raphael Helfand

For the better part of the past decade, Cooper B. Handy has been moonlighting as Lucy. Cooper is a 27-year-old food service worker in western Massachusetts; Lucy is a singer-producer from a planet where honesty is a natural state and soul-baring is approved of, as long as one can accomplish it with a sense of humor. (Other inhabitants of this world include Jonathan Richman and Young Thug.) But the differences end there. Cooper and Lucy are symbiotes, living in harmony in one lanky body. And their relationship is far from secret: Until Friday—when he dropped his studio debut, The Music Industry Is Poisonous—Lucy had named all but one of his self-recorded, self-produced, and self-released solo records (Cooper B. Handy’s Album, Vols. I-VII) after his host.

Lucy first entered the semi-public sphere of 20-year-old hipsters around 2014, as a member of the hip-hop collective Dark World. They were actually a relatively diverse outfit—as diverse as could be expected in Hampshire County, MA, at least—but it existed in the shadow of its charismatic leader, DJ Lucas, the uncrowned king of white guy irony rap. Throughout the mid-‘10s, the Dark World crew gained clout in western Mass, Brooklyn, and colleges nationwide, operating in overlapping circles—and sometimes joining forces—with groups like Ratking and Secret Circle. But their rise was short-lived. Much of the collective’s core demographic entered the workforce, started relationships with partners unenamoured by edgy hip-hop, and put their DJ Lucas tapes into storage. If Dark World is still operating at all, it is far from the force it used to be.

Cooper and Lucy got out before the crew hit rock bottom, but the one-man duo’s fanbase was still microscopic. They released their music solely on Soundcloud and bandcamp. They continued to grow their audience incrementally with captivating live shows—picture a happy John Maus, moving spasmodically behind the same translucent fourth wall of awkward energy, but without all the hair-pulling, chest-punching, howling, and other signs of deep unwellness. But they seemed uninterested in gaining national recognition. Then, in 2018, Cooper signed with independent label Dots Per Inch Music. DPI put a chunk of Lucy’s catalog on the major streaming platforms and later released a 16-track greatest hits compilation for radio promotion (aptly titled Radio Edit).

Lucy’s luck seemed to be taking an upward turn in spring 2020, when world-famous sadboy crooner King Krule recruited him as an opener for the East Coast portion of his US spring tour, but something else happened in the US in March that spoiled those plans for the foreseeable future. The Music Industry Is Poisonous, set to be released in September for a new generation of hybrid King Krule/Lucy fans, was pushed back indefinitely. Of the many music careers stunted by the pandemic, Cooper’s seemed to be the victim of an especially merciless fate. Still, he and his symbiote took it in stride, using the ensuing year of lockdown as an opportunity to work on their backlog, make a series of gorgeous music videos with director Guy Kozak, and release a tremendously fun collab with Palberta’s Lily Konigsberg.

I spoke to Cooper in late April, on the eve of his new album’s release. He seemed nervously hopeful, and though he emphasized that he did not want The Music Industry Is Poisonous to have “any kind of debut vibes,” I sensed a barely-contained excitement for the next chapter of Lucy’s life. Our conversation often devolved into personal anecdotes and jokes, but we managed to discuss career moves, Cape Cod, catering and The Clash over the course of 45 minutes that felt like the blink of an eye.

RAPHAEL: I first found your music through Dark World, which my friends and I were pretty into back in college. I ended up growing out of that phase, to the point that you're pretty much the only one I still follow from that group. You eventually grew out of it too, it seems. What was that experience like?

COOPER: It was an interesting way to get into the idea of making music with a bunch of people, which was pretty foreign to me. I'd played in bands before, but I'd never really been around a collective like that. It was definitely exciting as a teenager. But it's really hard to make it as a group. I think the same thing happens with a lot of collectives. It's hard to work with other people towards the same goal. Everyone starts to have different goals as time goes on.

In the writing I've read on your music—which there isn't much of yet—people zero in on your earnestness, as opposed to all the irony in hip-hop adjacent music made by young white guys over the past few years. They seem to be differentiating you from specifically that Dark World aesthetic.

Yeah, it gets into a kind of funny realm... I don't know. I listen to a lot of music that has funny elements, but I try to at least keep the lyrics in my own music not too jokey. I never really think of my music as funny that way, but there are people who tell me my music makes them laugh in a way that's not silly.

I think there's a healthy mix of silly and serious. Like, you’ve got some serious tracks on this album, but there’s also "Turn Page," where you list all your elementary school teachers' names in the chorus.

[Laughs] Yeah, that one is definitely silly.

It's always one of the more serious tracks on each of your albums that ends up feeling like the standout to me: "Turbulence" and "Break Even" and "INLOVE WITH LIFE," for instance. "Believe" feels like the centerpiece on this one.

That was originally what I was thinking. I thought that song was going to stand out more than it ended up feeling like it did. But I always have different opinions on this album every time I listen back to it.

Well, it's been around for a while now.

It's definitely the longest I've ever sat on any music. It feels kind of crazy, but in the big picture, talking to other musicians and people who have worked for labels, it seems like it's pretty normal to have a whole time period with all this stuff.

I first heard this album almost a year ago, when it was all set to come out in fall 2020. That was after the tour with King Krule had already been cancelled, so I’m wondering why it was postponed, and why you and the label chose right now to finally release it.

It was a mix of things. COVID definitely had a lot to do with it, but we also had to do a couple passes of mixing and mastering. It's the first album where I've ever had anyone else involved with the way it sounds. I brought all the stems to Tom [Moore, founder of Dots Per Inch] at a studio in Maspeth [Queens] and they put them all in ProTools, which I had never used. It was mastered by Sarah Register, who has a really cool catalog. So I was just watching people do things that I didn't know how to do, or that I knew how to do, but only the GarageBand version. So it was a slower process. It was very foreign to me to have other people in the blend.

After all that, does this record feel like a fuller project to you than the other Cooper Handy albums?

I definitely hope it stands out because of the time put into it and the way it sounds. But thinking it's still a very short album, and the songs are still short, so I like to think that it's more part of the lineage than a standalone thing. I've been talking to Tom about this sort of thing through the whole project: I'm stoked to be taking things to a more serious level, but I also don't want it to have any kind of debut vibes. That's been a hard thing for me since the beginning of deciding to sign. I don't want it to seem like I'm like a new artist.

You’ve been part of some great collaborations, most recently the split record with Lily Konigsberg. Some of my favorites have been the ones you’ve done with Gods Wisdom. I know you've been working with him for a long time now, since y'all were both in Dark World. Can you talk about that relationship and how it's changed since you both left the collective?

He's one of the only people I have an easy time making music with. A lot of the music I've made with him comes from beats that I would make for myself. It's all stuff I would be stoked to do solo too. I like how our voices are super different; it’s a good contrast. We have a couple of things on the horizon that we've been sitting on. One is a five-song EP we recorded like two years ago that's me on drums with brushes and him on piano. And then about a month ago, we finished a full 12-song collaboration record that we've been working on for like a year. I have a bunch of things I'm waiting on because I don't want to push anything. I know that it takes a while for a record to do its thing. I'm also in a band called Taxidermists that's just a two-piece—me on guitar and singing and my friend Sal[vador McNamara] on drums—and we’ve got some things planned. We've been playing together since we were 13 or 14. He's one of the only people from my childhood that's still in my life playing music with me. He grew up on Martha's Vineyard and I grew up in Falmouth, which is the town the boat to Martha's Vineyard leaves from.

I wanted to ask about your other life as a food service professional. You work at Amherst College, right?

Yeah. I've been there for like a pretty long time. It's a pretty easy job to stay at for me. I'm in the catering department, so I'm basically getting food from the kitchen, putting it in a warmer, and then putting that warmer in the back of a golf cart and driving it to whatever location on campus. That's kind of the whole job.

Did you work at restaurants growing up?

Not really. I started that job when I moved out to western Mass when I was 18. In high school, I only had two farm jobs. That was my only real set of work skills. I thought that I wanted to do that for a living until I started doing more music stuff and playing shows. I was like, "I can't be up at 6 a.m. doing farm stuff every day."

In the triple video you made with Guy Kozak, there's a part where you're in an apron in this really rustic-looking restaurant laying down an old school, red-and-white checkered tablecloth. When I first saw it, I wondered if that was a place you'd actually worked at.

That restaurant actually is in my hometown. It's called Silver Lounge. I only ate there like once growing up, but Guy's girlfriend grew up in the same town as me, and her parents knew the owner, so that's how we got access.

Is that how you and Guy linked up originally?

Yeah, he went with his girlfriend to see me play in New York, and then we started working together. It's really easy to work with him. He's pretty serious about it and really into the analog film thing, which is fun.

I love these videos, partly because they unlock this whole new aesthetic to your music and your performance that I hadn't considered before when all your videos were so grainy and DIY. But your music is actually very theatrical, so I think it makes perfect sense for your videos to be so cinematic and colorful.

At the beginning I was a little worried it might come off too clean because everything I'd done before was kind of blurry and we'd mostly used VHS. It was a lot more haphazard and crazy. So when I started working with Guy, I was like, "Oh no, I hope people don't think this is too twee." But the more I watched his stuff, the more I realized that it's pretty straightforward. I'm not acting too much or anything.

Let's talk a little about your process. Do you start with production or lyrics?

Usually I'll have some sort of riff in my head that'll end up being like the hook to a song. I'll record that as a voice memo on my phone, and then when I get home (or wherever else I'm at that has a keyboard), I'll figure out what I was singing and what chords go with that. Then I send that to an actual computer, and then, once the riff is there, I'll build a drum part that takes over as being like the important thing. I make sure to have the drums finished—A section/B section, or however it's formatted—and then I'll unmute the keyboard part and chop it up a bit to fit it where it goes. So melody first, but followed closely by drums.

Do you still use GarageBand?

Yeah.

As someone who once made music with GarageBand myself, I definitely used to recognize some of those preset instruments in your music. Not quite so much anymore.

Yeah, I try to stay away from those. The only GarageBand instrument I really use is the grand piano. And even that, a lot of times I just use it for a little touch; it's not the lead keyboard. Sometimes I'll use some [GarageBand] strings in the back, but I try to keep it not too MIDI, so it's mostly from an actual keyboard. There are some songs I've done where the more prominent parts are MIDI sounds from GarageBand, but I try to steer away from that and make sure that the root notes and the stuff holding down the track is coming from outside the computer.

Where do you get your drums, if you don't mind me asking?

A friend of mine made me a pack of cool drums, probably in like 2013. He gave me a folder that was like nine pieces from an 808 kit and six from a 707.

You've said that pop-punk was really formative for you growing up. Clearly you're not making pop-punk right now, but I think I can see how it factors into your music. Still, what you do is very different from the hip-hop/pop-punk fusion trend that's so popular today.

I think it's a hard thing to have that comparison these days, because it is super common now. There's a lot of trap artists who are almost overly blatant about referencing those bands. I think it's cool, and It makes a lot of sense to me, but it's a hard comparison to stick to. At the same time, [pop-punk] is the music that made me realize I wanted to make music, so I don't want to deny it as a thing that matters to me.

I'm excited to see what happens with music in general. It's moving at a quick pace, and I'm definitely happy about it. A lot of people I'm around are like, "Man, what's going on with music? It's all messed up!" But at this point I'm kinda just stoked for everything. People are picking up the tempo in a way that I wanted them to 10 years ago. People are making fast music that's a lot more crazy.

I mean, that's the perennial bad hip-hop take: Whatever is happening at the moment is awful and everyone should just listen to Biggie. I definitely felt that way for a long time, but it's stupid. Are there any rappers or producers you particularly admire, either current or from back in the day?

I do listen to a ton of new hip-hop, but there's also a lot of older rappers I come back to. Someone like Lil Wayne, I'm always down to go back and listen to his music. And Chief Keef is someone I can always bounce back to. There's a lot of cool things happening with rap vocals right now. I feel like 2012—the Young Thug era, when everyone was starting to sing—was the big turning point. That was what opened the floodgates for tons of music. Totally. He's the reason so much stuff is the way it is: obviously Young Thug, but also, like, Drake. It's crazy listening to early Drake because his whole voice is literally just Wayne.

On the pop-punk side, are there any bands you loved growing up that you still listen to?

I'm always listening back to certain stuff. I was super into Green Day, and that was the first concert I went to: 2004, American Idiot tour. That was really big for me, but Green Day's a little harder for me to listen back to, for some reason. With Blink-182, for instance, I can listen to a bunch of their records; there's something a little more potent to them. The Clash are another group—different era, obviously, but precursors to all this pop punk stuff. They were also one of the first bands that I was like, "Oh, I wanna be able to play music like this." I consider them pop-punk too.

I feel like people don't talk about The Clash much anymore.

I feel like that too. I think it's a weird thing with music people. A lot of my friends who are music heads, or whose parents are music heads, didn't grow up listening to them. I don't think they're that revolutionary or anything, but I do think they're under-talked-about. [Laughs].

I think nowadays people talk a lot more about early American punk—

—which I also love.The first few Ramones records, that's the best driving music.

The last thing I want to talk about is your live show. The one time I saw you it was just you singing and dancing with a backing track. It's hard to sell that, but your energy made it work. When you go back to playing live shows, do you intend to stick with that set-up? Would you consider bringing a band in?

I'll definitely stick with it for a while. I love just having a backing track being able to do my thing. But down the line, I think about having a band that's got drums, a stand-up bass, a piano player, and me singing. That's something I see myself doing in 10 years.

Raphael Helfand is Laid Off NYC's Editorial Director and co-edits our Music section. Get to know him better: @raphael_helfand

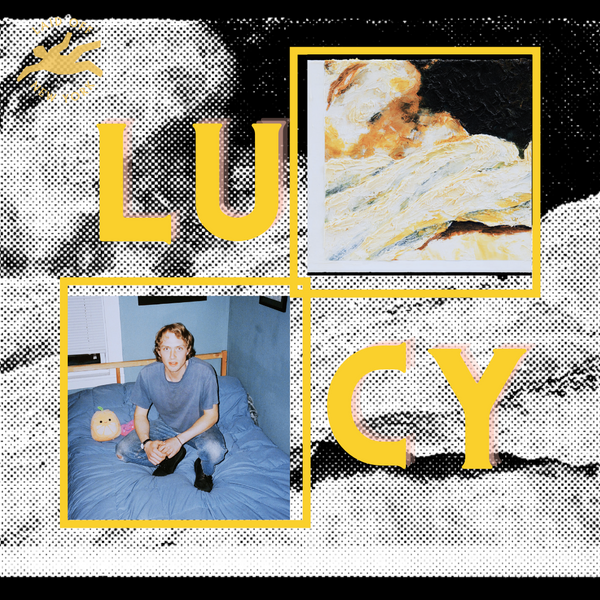

*Thumbnail graphic created by Jda Gayle includes a Lucy press shot by Annabell P. Lee and The Music Industry is Poisonous album cover.